1 Introduction

In recent times, focused remedy has achieved vital success in superior non-small cell lung most cancers (NSCLC). Sufferers with metastatic lung most cancers who qualify for focused therapies now expertise extended survival, with 5-year survival charges starting from 15% to 60%, contingent on the precise biomarker recognized (1–4). Consequently, molecular and immune biomarker testing of lung most cancers specimens is essential to figuring out doubtlessly efficient focused remedies, particularly in sufferers with metastatic NSCLC (3–7). It goals to alleviate signs, lower tumor burden, and enhance total survival (OS).

Traditional actionable biomarkers included numerous genetic alterations which are the targets of a number of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) equivalent to anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement, V-RAF mouse sarcoma virus oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) p.V600E mutation, epidermal development issue receptor (EGFR) mutation, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2, also called human epidermal development issue receptor 2, HER2) mutation, Kirsten rat sarcoma virus (KRAS) mutation, mesenchymal-epithelial transition issue (MET) exon 14 (METex14) skipping mutation, neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase 1/2/3 (NTRK1/2/3) gene fusion, rearranged in transfection (RET) rearrangement, receptor tyrosine kinase ROS proto-oncogene 1(ROS1) rearrangement, and high-level MET amplification. These gene alterations usually happen in a non-overlapping method. Nonetheless, 1%–3% of sufferers could have coexistence of multiple of those biomarkers (8).

Right here we summarize the important therapeutic targets and focused medication for NSCLC (Desk 1) and supply insights into the therapy response and resistance mechanisms related to focused therapies.

2 Biomarkers and goal therapies

2.1 EGFR inhibitors

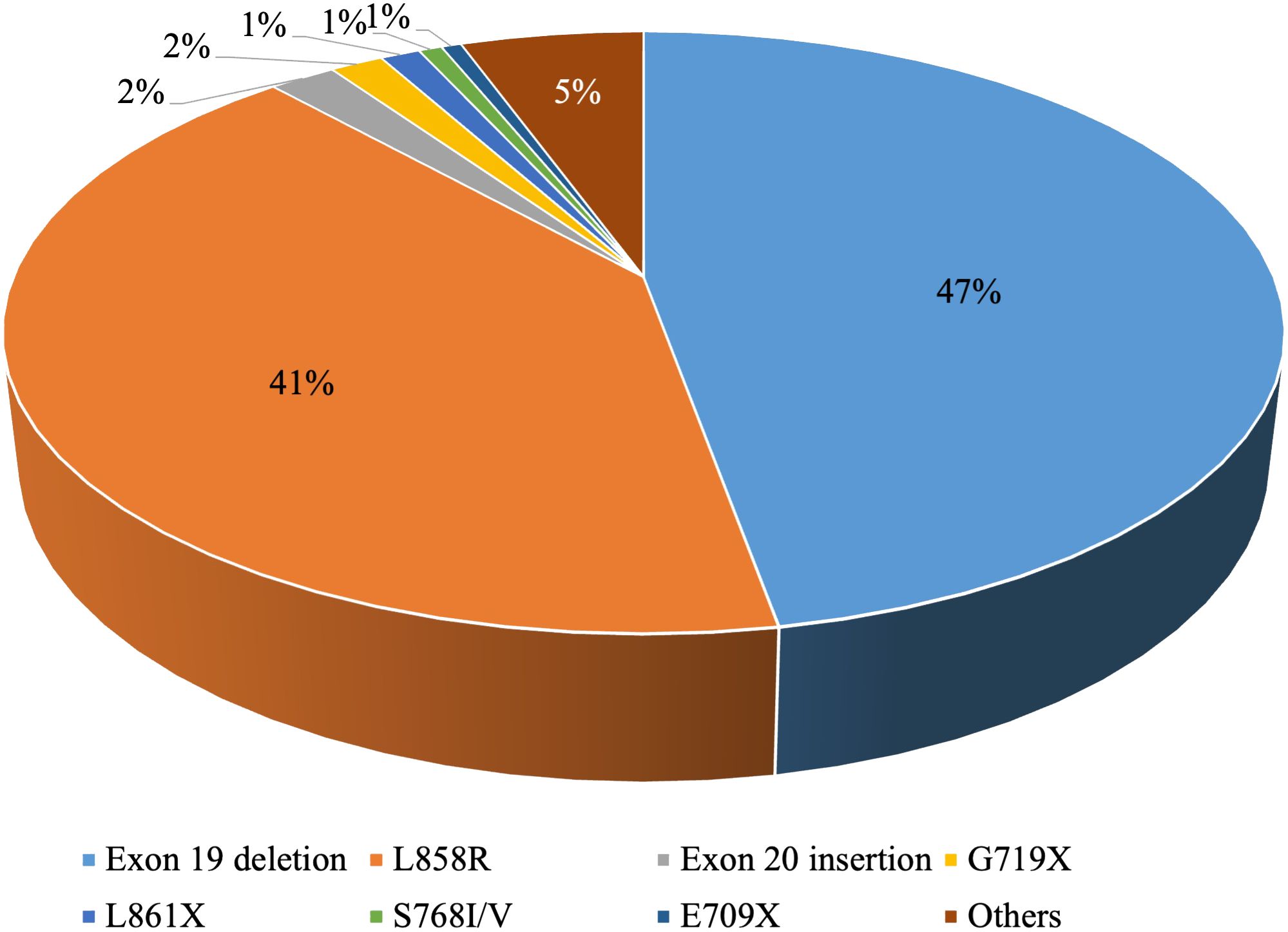

EGFR is the most typical driver gene in NSCLC. The mutation frequency is roughly 10-15% in Western Europe and North America and might be as excessive as 30%-50% in East Asia (9, 10). Widespread EGFR mutations contain exon 19 deletions and the exon 21 mutation p.L858R, whereas much less frequent mutations embrace p.S768I/V, p.L861X, and p.G719X (11) (Determine 1).

2.1.1 First-generation drugs

Gefitinib and erlotinib have been each reversible inhibitors of the first-generation EGFR TKIs. They’ll selectively and reversibly forestall ATP binding, thereby inhibiting EGFR autophosphorylation (12). An evaluation of 5 medical research during which erlotinib or gefitinib was used as first-line therapy in NSCLC (stage IIIB or IV) revealed that the response fee was 67% in sufferers with sensitizing EGFR mutations (13).

2.1.1.1 Erlotinib

Erlotinib has proven higher efficacy than typical chemotherapy in superior NSCLC sufferers with EGFR mutations in a number of randomized section III trials. Within the EURTAC trial, sufferers receiving erlotinib demonstrated a response fee of 58% with a median PFS of 9.7 months, whereas these receiving typical chemotherapy exhibited a response fee of 15% with a median PFS of 5.2 months (14). Within the trial CALGB30406, erlotinib monotherapy achieved a powerful response fee of 70% (15). One other section III trial reported the next goal response fee within the gefitinib group in comparison with the chemotherapy group (73.7% vs. 30.7%) (16).

2.1.1.2 Gefitinib

The section III randomized trial IPASS evaluated the efficacy of gefitinib in beforehand untreated NSCLC sufferers in East Asia, sufferers handled with gefitinib exhibited a considerably excessive goal response fee of 71.2% in comparison with these handled with carboplatin–paclitaxel (17). The OPTIMAL trial additionally reported a superior response fee within the gefitinib group in comparison with the chemotherapy group (83% vs. 36%) (18). The section III randomized trial WJOG5108L reported related response charges for gefitinib and erlotinib at 55.0% and 58.9%, respectively (19).

2.1.2 Second-generation drugs

2.1.2.1 Afatinib

Afatinib, a second-generation oral TKI, exerts irreversible inhibition focusing on the ErbB/HER receptor household together with EGFR and HER2 (20). In a section IIB trial evaluating afatinib and gefitinib for first-line therapy in widespread EGFR mutation metastatic adenocarcinoma sufferers, afatinib demonstrated a considerably increased goal tumor response fee in comparison with gefitinib (70% vs. 56%) (21). Up to date outcomes revealed no vital distinction in OS between the 2 teams (22). A subgroup evaluation of a number of LUX-LUNG trials (LUX-LUNG 2, 3, and 6) evaluated the efficacy of afatinib in sufferers with mutation-positive metastatic NSCLC. The response fee was 77.8% in sufferers with EGFR p.G719X mutation, 100% in p.S768I, and 56.3% in p.L861Q (23). Notably, these findings needs to be interpreted cautiously as therapy crossover occurred in most sufferers (72% in LUX-LUNG 3 and 80% in LUX-LUNG 6).

2.1.2.2 Dacomitinib

Dacomitinib is a second-generation oral TKI, that exerts irreversible inhibition on ErbB/HER receptors, together with EGFR, HER1, HER2, and HER4.Within the section III randomized trial ARCHER1050, sufferers receiving dacomitinib as first-line therapy exhibited an goal response fee of 75% (24). Subsequent up to date information indicated that dacomitinib-treated sufferers skilled longer progression-free survival (PFS) (14.7 months vs. 9.2 months) and OS (34.1 months vs. 27 months) in comparison with the gefitinib group (25, 26).

2.1.3 Third-generation drugs

Roughly 60% of sufferers who progressed on first- and second-generation EGFR TKI therapy harbor EGFR p.T790M mutation. The third-generation EGFR TKIs have been initially designed to beat the resistance attributable to acquired EGFR p.T790M mutation. Osimertinib, an oral and irreversible TKI, reveals selectivity for each widespread EGFR mutations and p.T790M mutation, with exercise throughout the central nervous system (CNS) (27–29). Osimertinib is the primary third-generation EGFR-TKI authorised by the Meals and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Company (EMA) for metastatic NSCLC sufferers with EGFR p.T790M mutation (30).

In a section III randomized trial (AURA3), involving sufferers with EGFR p.T790M-positive metastatic NSCLC progressing after first-line therapy, the target response fee was considerably superior with osimertinib (71%) in comparison with chemotherapy (31%). Osimertinib additionally exhibited an extended PFS (10.1 vs. 4.4 months). Notably, within the subgroup of sufferers with CNS metastases, osimertinib offered a protracted PFS in comparison with these handled with platinum–pemetrexed (8.5 vs. 4.2 months) (31). The BLOOM examine which elevated the usual dose of osimertinib from 80 mg as soon as every day to 160 mg as soon as every day, have proved helpful of the upper dose of osimertinib for sufferers with leptomeningeal illness development with EGFR mutations, no matter p.T790M standing, with an goal response fee of 62% (32, 33).

Along with the second- or third-line use to beat resistance of first- and second-generation EGFR TKI therapy, osimertinib has been used as first-line to deal with EGFR mutant NSCLC sufferers. A Multicenter, Part II Trial (KCSG-LU15-09) demonstrated an goal response fee of fifty% for osimertinib as first-line therapy in 37 sufferers with EGFR uncommon mutations, together with p.S768I, p.L861Q, and p.G719X (34). The section III randomized trial (FLAURA) additionally proved an extended median OS with osimertinib as first-line therapy than with erlotinib or gefitinib (38.6 months vs. 31.8 months), although the target response fee was comparable (80% vs 76%) (35, 36).

2.1.4 Different drugs

2.1.4.1 Amivantamab

Amivantamab is a bispecific human antibody to each EGFR and MET receptors that bypasses resistance to EGFR TKIs (37). CHRYSALIS examine, a section I examine, evaluated the efficacy of Amivantamab-vmjw as a subsequent therapy in 81 metastatic NSCLC sufferers with EGFR exon 20 insertion. The general response fee reported on this cohort was 40% (37). In a section III examine (PAPILLON), amivantamab-chemotherapy considerably improved PFS of sufferers with EGFR exon 20 insertions who had not acquired earlier systemic remedy when in comparison with chemotherapy alone (median, 11.4 months and 6.7 months, respectively) (38). And MARIPOSA evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of Amivantamab plus carboplatin-pemetrexed (chemotherapy) with and with out Lazertinib in sufferers with EGFR-mutated (exon 19 deletions or L858R) regionally superior or metastatic NSCLC after illness development on Osimertinib. The median PFS was considerably longer for amivantamab-chemotherapy and amivantamab-lazertinib-chemotherapy versus chemotherapy (6.3 and eight.3 versus 4.2 months, respectively) (39).

2.1.4.2 Mobocertinib

Mobocertinib is an oral TKI selectively inhibiting EGFR and HER2 exon 20 insertion mutations (40, 41). A section I/II examine evaluated the efficacy of mobocertinib as a subsequent therapy in sufferers with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutation. The target response fee was 28%, with a median length of response of 17.5 months and a median PFS of seven.3 months (40). Subsequently, mobocertinib acquired FDA accelerated approval for superior or metastatic NSCLC in adults with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations who progressed throughout or after platinum-based chemotherapy.

Nonetheless, outcomes from the section III trial, EXCLAIM-2, indicated that the target response charges and illness management charges between the mobocertinib and chemotherapy teams are related (response fee: 32% vs. 30%, management fee: 87% vs. 80%) (42). In consequence, the FDA and Takeda withdrew mobocertinib in America in October 2023, because it didn’t meet the first endpoint of the examine.

2.1.4.3 Cetuximab

Cetuximab is a monoclonal antibody to EGFR. In a big section III randomized trial, FLEX, the mixture of chemotherapy and cetuximab proved increased total response charges than chemotherapy alone (36% vs. 29%) and comparable median OS (11.3 vs. 10.1 months) (43). Nonetheless, this mix exhibited poorer tolerability contemplating the almost 40% incidence of grade 4 neutropenia. Subsequently, the usage of cetuximab will not be but really helpful in NSCLC.

2.2 ALK inhibitors

ALK gene rearrangements occurred in roughly 3-5% of NSCLC sufferers (44). To date, greater than 19 distinct ALK fusion companions have been recognized in NSCLC, together with EML4, KIF5B, KLC1, and TPR (45). The commonest fusion was EML4::ALK, present in about 85% of ALK-rearrangement NSCLC.

2.2.1 First-generation drugs

2.2.1.1 Crizotinib

Crizotinib is a first-generation oral TKI and the primary TKI authorised for treating ALK-positive NSCLC, successfully inhibits ALK rearrangements, ROS1 rearrangements, high-level MET amplification, and METex14 skipping mutations. In section I and II research, crizotinib demonstrated goal tumor responses in roughly 60% of ALK-positive NSCLC sufferers, with a median PFS starting from 7 to 10 months (46–48). A section III randomized examine, PROFILE 1014, assessing the efficacy of crizotinib as first-line focused remedy, yielded promising outcomes with an goal response fee of 74% (49). For ALK-positive sufferers progressing after first-line chemotherapy, crizotinib has proven efficacy in enhancing PFS (7.7 months) and enhancing response charges (65%) (50).

2.2.2 Second-generation drugs

2.2.2.1 Alectinib

Alectinib is a selective second-generation oral ALK inhibitor with excessive CNS penetration. It has demonstrated exercise in opposition to a number of secondary mutations related to acquired resistance to crizotinib, equivalent to p.T1151L, p.1152insT, p.L1196M, p.C1156Y, p.F1174L, and p.G1269A (51, 52).

The ALEX trial, a section III randomized examine, in contrast the efficacy of alectinib and crizotinib as first-line remedies in 303 ALK-positive superior NSCLC sufferers, together with these with asymptomatic mind metastases. The response fee within the alectinib group was 82.9% and 75.5% within the crizotinib group (53). One other section III trial, J-ALEX, enrolled 207 ALK inhibitor-naive Japanese sufferers with ALK-positive NSCLC, additionally proved that alectinib as a first-line therapy achieved the next goal response fee in comparison with crizotinib (92% vs. 79%) (54).

Efficacy of alectinib as subsequent remedies was reported by section II trials with a complete response fee of 48% to 50% in metastatic NSCLC sufferers with ALK rearrangement progressing after crizotinib therapy (55, 56).

2.2.2.2 Brigatinib

Brigatinib is a second-generation TKI that inhibits a broad spectrum of ALK rearrangements. As first-line therapy, brigatinib was reported the next systemic goal response fee of 71% than crizotinib (60%) within the ALTA-1L trial. The intracranial response fee was additionally notably increased with brigatinib (78%) in comparison with crizotinib (29%) (57). Up to date information additional confirmed that the 3-year PFS within the brigatinib group was superior to crizotinib (43% vs. 19%) (58).

A section II examine, ALTA, evaluated the efficacy of two totally different doses of brigatinib in ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC sufferers who had skilled illness development on or intolerance to crizotinib. The general response fee ranged from 45% to 54%. In sufferers with measurable mind metastases, the intracranial total response fee was noticed to be between 42% and 67% (59, 60).

2.2.2.3 Ceritinib

Ceritinib is a second-generation oral TKI designed for ALK and ROS1 rearrangements (61), displaying promising leads to numerous medical trials. Within the ASCEND-4 trial, the general response to ceritinib as first-line remedy was 72·5% with a median PFS of 16.6 months, as in contrast with 26·7% with a median PFS of 8.1 months within the chemotherapy group (62).

As subsequent therapy in sufferers with prior publicity to at the very least two remedies, ceritinib was reported an total response fee of 38.6%, with a concurrent intracranial response fee of 45.0% in a section II examine (ASCEND-2) (63), and the next total response fee of 45% than pemetrexed or docetaxel chemotherapy (8%) (64).

2.2.3 Third-generation drugs

Lorlatinib, a third-generation oral TKI with glorious CNS penetration, selectively inhibits ALK and ROS1. It reveals the power to inhibit ALK resistance mutations that emerge following therapy with first and second-generation ALK inhibitors (65–68). Within the section III randomized trial, CROWN, lorlatinib demonstrated full CNS responses in 61% of sufferers with baseline mind metastases, in comparison with solely 15% with crizotinib (69). Up to date information reveals a decrease cumulative CNS development fee with lorlatinib (7%) than crizotinib (72%) over 12 months, and better 1-year PFS charges of 78% than 22% for crizotinib in sufferers with mind metastases (70).

Lorlatinib additionally stays efficient for sufferers experiencing development after therapy of different ALK inhibitors, particularly these with CNS involvement. Amongst sufferers with measurable baseline CNS lesions, 47% achieved goal responses, and 63% achieved an goal intracranial response (66, 67).

2.3 BRAF inhibitors

BRAF mutations manifest in 1%–5% of NSCLC sufferers (71–74). The commonest mutation is p.V600E, accounting for roughly 50% of BRAF-mutated circumstances (75). Different BRAF mutations embrace p.D594G and p.G469A/V, noticed in 35% and 6% of BRAF-mutated NSCLC sufferers, respectively (74). For NSCLC sufferers with p.V600E mutation, the FDA has at the moment authorised two combos of RAF and MEK inhibitors: dabrafenib/trametinib and encorafenib/binimetinib.

2.3.1 Dabrafenib/trametinib

In a section II trial, dabrafenib/trametinib as first-line therapy demonstrated a sturdy total response fee of 64% in 36 sufferers with BRAF p.V600E mutation (76). An up to date evaluation of this trial revealed a 5-year OS fee of twenty-two% (1). One other dual-cohort section II examine carried out a comparative evaluation between sufferers receiving dabrafenib monotherapy and mixture remedy with dabrafenib and trametinib. The outcomes indicated a definite total response fee of 33% and 67%, and median PFS durations of 5.5 months and 10.2 months, respectively (77).

2.3.2 Encorafenib/binimetinib

Within the PHAROS trial, an open-label, multicenter, single-arm examine, a powerful total response fee of 75% was noticed among the many 59 treatment-naive sufferers with BRAF p.V600E mutation, with a median length of response not achieved. Within the cohort of 39 beforehand handled sufferers, the general response fee was 46%, and the median length of response was 16.7 months (78).

2.4 ERBB2 (HER2) inhibitors

2.4.1 Ado-trastuzumab emtansine

Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine, also called T-DM1, is a humanized antibody-drug conjugate comprising the HER2-targeting antibody trastuzumab and the microtubule inhibitor emtansine (79). In a section II basket trial, the efficacy of ado-trastuzumab emtansine was assessed in sufferers with metastatic NSCLC and HER2 mutations, revealing a partial response fee of 44% (79, 80). One other examine targeted on sufferers with HER2 exon20 insertion mutations, indicating an goal response fee of 38% with ado-trastuzumab emtansine (81). These findings underscore the potential of ado-trastuzumab emtansine as a focused therapeutic possibility for sufferers with HER2-mutated NSCLC.

2.4.2 Fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki

Fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki, a humanized monoclonal antibody-drug conjugate comprising trastuzumab linked to deruxtecan, is a topoisomerase I inhibitor (82). A section I trial investigated the efficacy of fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki in HER2-mutant NSCLC sufferers, representing an goal response fee of 72.7% (83). The DESTINY-Lung01, a section II examine, revealed an goal response fee of 55% in 91 sufferers handled with fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki (82).

2.5 KRAS inhibitors

KRAS mutations are recognized in roughly 30% of NSCLC sufferers (84). These mutations are predominantly (>95%) situated at codons 12 and 13. The p.G12C variant was probably the most prevalent, constituting 39% of all KRAS mutations, adopted by p.G12V (21%) and p.G12D (17%) variants (85). Sotorasib and adagrasib are each an oral inhibitor to the RAS GTPase household, demonstrating efficacy in inhibiting the KRAS p.G12C mutation in sufferers with metastatic NSCLC who’ve beforehand undergone chemotherapy (± immunotherapy).

2.5.1 Sotorasib

Sotorasib, as a small-molecule inhibitor, irreversibly binds to the non-active GDP pocket of KRAS, forming an irreversible covalent bond with the cysteine residue in KRAS p.G12C. This covalent interplay locks the protein in an inactive state. By disrupting the KRAS signaling pathway, sotorasib inhibits cell development in addition to tumor development each in vitro and in vivo and induces apoptosis in KRAS p.G12C tumor cell traces (86, 87).

In a section II examine involving 126 sufferers with KRAS p.G12C-positive superior NSCLC who had prior platinum-based chemotherapy (with or with out immunotherapy), subsequent therapy with sotorasib confirmed a partial response fee of 33.9% and full response fee of 4.2% (88). The section III randomized examine, CodeBreaK200 trial, has additionally reported the efficacy of sotorasib in sufferers in an analogous scenario (89). Sotorasib demonstrated a considerably increased total response fee of 28.1% than docetaxel (13.2%). Furthermore, the disease-control fee within the sotorasib group was 82.5%, in comparison with 60.3% within the docetaxel group.

2.5.2 Adagrasib

In a section II examine involving 116 sufferers who had beforehand undergone platinum-based chemotherapy with or with out immunotherapy, adagrasib demonstrated an goal response fee of 42.9%. The efficacy of adagrasib in circumstances with KRAS mutations past p.G12C stays to be systematically evaluated (90).

2.6 MET inhibitors

The oncogenic driver genomic alterations related to MET comprise METex14 skipping mutations and high-level MET amplification. Excessive-level MET amplification was lately recognized as an rising biomarker. Its definition could fluctuate relying on the reagent kits. When using Subsequent-Era Sequencing (NGS), high-level MET amplification is outlined because the copy quantity higher than 10 (91). The FDA has not but authorised really helpful medication for NSCLC sufferers carrying these mutations, regardless of their approval in different tumor sorts.

2.6.1 Capmatinib

Capmatinib is an oral TKI selectively focusing on MET alterations. The GEOMETRY trial revealed that capmatinib achieved an total response fee of 68% as a first-line therapy, and 41% as subsequent therapy in sufferers with METex14 skipping mutations. Whereas in sufferers with high-level MET amplification, the response fee was 40% because the first-line remedy, and 29% as subsequent remedy (91). Notably, the up to date information of GEOMETRY point out that capmatinib reveals anti-tumor efficacy throughout the mind (92). One other examine revealed an total response fee of fifty% in a cohort of 10 sufferers with high-level MET amplification (93).

2.6.2 Crizotinib

Crizotinib is an oral TKI that inhibits METex14 skipping mutation and high-level MET amplification. A section II examine evaluated the efficacy of crizotinib in 69 sufferers with METex14 skipping mutations. The target response fee was 32%, with a median PFS of seven.3 months (94). The PROFILE1001 examine investigated the efficacy of crizotinib in superior NSCLC sufferers with various ranges of MET amplification. Sufferers with MET genomic copy quantity over 10 demonstrated an total response fee of 29% (95).

2.6.3 Tepotinib

Tepotinib is a selective oral TKI that inhibits METex14 skipping mutation and high-level MET amplification. A section II examine (VISION) assessed the efficacy of tepotinib in sufferers with MET mutations. The response fee in sufferers with METex14 skipping mutations was 46%. One other cohort comprising 24 sufferers with MET amplification however missing METex14 skipping mutations exhibited an total response fee of 41.7% (96, 97).

2.7 NTRK1/2/3 inhibitors

NTRK1/2/3 gene fusions encode TRK fusion proteins, serving as oncogenic drivers in a number of stable tumors, together with lung, thyroid, salivary gland, and sarcoma (98). Entrectinib and larotrectinib are each inhibitors of TRK fusion proteins in unresectable or metastatic stable tumors.

2.7.1 Entrectinib

The efficacy of entrectinib was evaluated in three section I or II trials (STARTRK-2, STARTRK-1, ALKA-372-001). A pooled evaluation revealed an total response fee of 70% in 10 NTRK gene fusion-positive NSCLC sufferers handled with entrectinib (99–101).

2.7.2 Larotrectinib

A examine comprising 55 sufferers with numerous stable tumors and constructive NTRK gene fusions revealed an total response fee of 75% with larotrectinib (98). The up to date information demonstrated that 90% of sufferers nonetheless remained alive one 12 months after therapy. Moreover, amongst 35 NTRK fusion most cancers sufferers, the general response fee reached 74% (102).

2.8 RET inhibitors

The RET gene is noticed in 1-2% of all NSCLC sufferers with chromosomal rearrangements and is concerned in numerous fusion companions equivalent to KIF5B, TRIM33, CCDC6, and NCOA4 (103, 104).

2.8.1 Pralsetinib

In a section I/II examine (ARROW), pralsetinib was assessed in metastatic NSCLC sufferers with RET rearrangements. The general response fee of pralsetinib was 70% as a first-line therapy, and 61% as a subsequent therapy reached 61% (105). The FDA authorised pralsetinib in 2020 for the therapy of metastatic RET fusion-positive NSCLC sufferers. It’s the first oral TKI focusing on RET fusions (106).

2.8.2 Selpercatinib

A section I/II examine, Libretto-001, together with its up to date outcomes, reveals that selpercatinib reveals outstanding efficacy in NSCLC sufferers with RET rearrangements. The general response fee for first-line therapy was 85%, whereas 64% for subsequent therapy. Notably, in sufferers with mind metastases, selpercatinib demonstrated effectiveness in 91% of circumstances (107, 108).

2.8.3 Cabozantinib

In a potential section II trial involving 26 RET fusion-positive sufferers handled with cabozantinib, the general response fee was 28% (109, 110).

2.9 ROS1 inhibitors

2.9.1 Crizotinib

Crizotinib is a multitargeted inhibitor focusing on MET, ALK, and ROS1. In an early-phase examine, crizotinib demonstrated appreciable efficacy in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC (111). The target response fee within the growth cohort handled with crizotinib reached 72%. The general response length was 17.6 months, with a median PFS of 19.2 months (112).

Three section II research confirmed an total response fee of greater than 70% with crizotinib in sufferers with ROS1 rearrangement. A section II trial evaluating the efficacy of crizotinib in 127 East Asian sufferers reported an total response fee of 72% (113). The PROFILE 1001 examine and up to date information reported an goal response fee of 72% in 53 ROS1-positive superior NSCLC sufferers, together with 3 full responses and 33 partial responses (4, 114). The multicenter trial, EUCROSS examine, reported a complete response fee of 70% in 30 sufferers handled with crizotinib (115). Moreover, a retrospective examine assessing crizotinib in stage IV ROS1-rearranged NSCLC sufferers (n=30) reported an total response fee of 80%, with a median PFS of 9.1 months (116).

2.9.2 Lorlatinib

Lorlatinib is an oral third-generation TKI focusing on each ALK and ROS1 with vital CNS penetration. It was evaluated in a section I/II trial for its efficacy in ROS1-positive metastatic NSCLC sufferers. The target response fee in sufferers beforehand handled with crizotinib reached 35%, whereas treatment-naive sufferers demonstrated a 62% goal response fee. Notably, intracranial responses have been noticed in 50% of sufferers with prior crizotinib therapy and 64% of treatment-naive sufferers (65).

2.9.3 Entrectinib

Entrectinib is an oral TKI inhibiting a number of tyrosine kinases, together with ROS1 and TRK. A pooled evaluation of 53 sufferers with ROS1 rearrangement throughout a number of section I and II trials (STARTRK-2 trial, STARTRK-1 trial, ALKA-372-001 trial) who acquired entrectinib as first-line therapy demonstrated an total response fee of 77%, with a 55% intracranial response fee (100, 101, 117). Though entrectinib reveals superior CNS penetration in comparison with crizotinib, it comes with increased toxicity, with an incidence of grade 3 or 4 adversarial occasions of 34% (117).

2.9.4 Ceritinib

Ceritinib is a second-generation oral TKI inhibiting ALK and ROS1 rearrangements. In a section II trial assessing ceritinib as first-line therapy in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC sufferers (28 evaluable sufferers), the reported total response fee was 62%, with 1 case of full response and 19 circumstances of partial responses (61).

2.9.5 Repotrectinib

A section I/II trial assessed the efficacy and security of repotrectinib in sufferers with superior ROS1 fusion-positive NSCLC. The confirmed total response fee was 79% amongst ROS1 TKI-naive sufferers and 38% amongst sufferers beforehand handled with different ROS1 inhibitors. Notably, responses have been noticed in intracranial lesions in sufferers with measurable CNS metastases, in addition to in these with resistance mutations following TKI remedy (118).

2.10 VEGF or VEGF receptors inhibitors

2.10.1 Bevacizumab

Bevacizumab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody focusing on VEGF. In a section III randomized trial, ECOG4599, involving relapsed or superior non-squamous NSCLC, the corresponding response charges have been 35% in sufferers handled with a mix of bevacizumab chemotherapy and 15% in these handled with chemotherapy alone (119). One other section III trial, NEJ026, in contrast the efficacy of erlotinib mixed with bevacizumab to erlotinib monotherapy as first-line remedies in EGFR-positive superior non-squamous NSCLC sufferers. The target response charges have been related (erlotinib/Ramucirumab: 72% vs. erlotinib monotherapy: 67%) (120).

2.10.2 Ramucirumab

Ramucirumab is a recombinant monoclonal antibody focusing on VEGF receptors. Within the section III randomized trial RELAY, first-line therapy with erlotinib/ramucirumab was in comparison with erlotinib monotherapy in EGFR-mutated superior NSCLC sufferers. The general response charges have been related (erlotinib/ramucirumab: 76% vs. erlotinib monotherapy: 75%) (121). The REVEL trial, a section III randomized examine in metastatic NSCLC sufferers who skilled illness development, evaluated the efficacy of ramucirumab/docetaxel in comparison with docetaxel alone as subsequent remedy. The ramucirumab/docetaxel group exhibited increased total response charges (23% vs. 14%) and illness management charges (64% vs. 53%) (122).

2.10.3 Nintedanib

Nintedanib is a potent, oral angiokinase inhibitor that targets the pro-angiogenic pathways mediated by VEGFR1-3 (123). Within the section III randomized managed trial LUME-Lung 1, 1314 stage IIIB/IV sufferers progressing after first-line chemotherapy have been randomly assigned to obtain docetaxel plus nintedanib (n=655) or docetaxel plus placebo remedy (n=659). PFS was considerably improved within the nintedanib plus docetaxel group when in comparison with the docetaxel plus placebo group (median 3.4 months vs. 2.7 months) (PMID: (124)).

3 Resistance to focused remedy

3.1 Overview of the mechanisms of resistance to focused therapies

Resistance to focused therapies is categorized as both major (intrinsic) or secondary (acquired) (125). Major resistance describes a de novo lack of therapeutic response, whereas secondary resistance signifies illness development after the preliminary response. Regardless of distinct resistance mechanisms recognized in sufferers with totally different gene alterations, there are widespread mechanisms shared amongst these cohorts (126). The acquired resistance mechanisms might be broadly categorized into two classes.

The primary class includes the event of extra genetic alterations within the major oncogenes, activating continued downstream signaling. That is typically attributed to secondary mutations in kinase targets or gene amplifications of the kinase itself (127). The second class of resistance improvement can happen independently of modifications within the goal gene. This situation contains upregulation of bypass signaling pathways, histological modifications of tumor tissue, or alterations in drug metabolism (128, 129). Furthermore, about 14% of small-cell lung most cancers can histologically rework into NSCLC, typically accompanied by resistance to the unique TKI (130, 131).

In 2010, Jackman et al. proposed the factors of acquired resistance in EGFR-mutant NSCLC (132): 1) Sufferers should have beforehand acquired EGFR inhibitor therapy. 2) Sufferers harbor both tumor-genotyping confirmed typical EGFR mutations related to drug sensitivity, or goal medical profit from therapy with an EGFR inhibitor. 3) Sufferers develop systemic development whereas on steady therapy with gefitinib or erlotinib throughout the final 30 days. 4) No extra systemic therapy between cessation of EGFR inhibitor and initiation of recent remedy.

3.2 Resistance to EGFR inhibitors

3.2.1 Major resistance

Major resistance to EGFR inhibitors could also be partially attributed to differential TKI sensitivity for various EGFR mutations. Typical EGFR mutations, together with exon 19 deletions and p.L858R, are related to vital sensitivity to TKIs (128). Conversely, exon 20 insertions or duplications, accounting for about 4% of sufferers with EGFR mutations, seem to have resistance to EGFR inhibitors (133).

3.2.2 Acquired resistance

The earliest report of TKI resistance in EGFR-mutant NSCLC recognized a substitution of threonine for methionine at residue 790 (p.T790M) (134). Subsequent reviews confirmed that p.T790M is the most typical mutation liable for TKI resistance, which is recognized in roughly 60% of sufferers who expertise illness development after preliminary response to first-line EGFR TKIs therapy (125, 134–140).

Threonine 790 serves because the “gatekeeper” residue, essential for inhibitor specificity within the ATP binding pocket. The p.T790M mutation prompts wild-type (WT) EGFR, introducing a rise within the ATP affinity of the p.L858R mutant by greater than an order of magnitude. That is the primary mechanism by which the p.T790M mutation confers TKI resistance, lowering the efficacy of any ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor. Irreversible inhibitors can merely overcome this resistance by means of covalent binding moderately than various binding (141). Subsequently, in sufferers with EGFR p.T790M-positive metastatic NSCLC experiencing development after first-line therapy, osimertinib as an irreversible EGFR-TKI can obtain an goal response fee of over 70% (31).

Different secondary mutations embrace p.D761Y, p.L747S, and p.T854A. They cut back the sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors, however the resistance mechanism stays unknown (142). Within the AURA trial, the acquired p.C797S mutation was noticed in 14% of the samples (31). The p.C797S mutation frequency was 7% when osimertinib was used as first-line remedy (35). The EGFR p.C797S mutation, during which cysteine at codon 797 is changed by serine within the ATP-binding website, leads to the lack of the covalent bond between osimertinib and mutated EGFR. Predictably, the p.C797S mutation additionally results in cross-resistance by stopping different irreversible third-generation TKIs from binding to the EGFR lively website (143–145).

TKI resistance might also activate bypass signaling pathways, equivalent to MET amplification (15-19%), PIK3CA mutations (6-7%), KRAS mutations (3%), and HER2 amplification (2-5%) (146, 147). Bypass pathway activation results in TKI resistance by sustaining activation of EGFR downstream signaling pathways.

3.3 Resistance to ALK inhibitors

The first resistance to ALK inhibitors could also be because of the totally different sensitivity of EML4::ALK variants and different ALK fusion genes to ALK inhibitors (148). Acquired resistance to ALK inhibitors usually happens throughout the first 12 months of therapy (125). Secondary mutations within the enzyme are the widespread mechanism of TKI resistance. It’s noteworthy that a number of secondary mutations can happen in ALK-positive sufferers upon TKI resistance. The primary “gatekeeper” mutation recognized within the EML4::ALK kinase area is p.L1196M (149). The substitution of leucine for methionine at place 1196 within the ATP binding pocket generates a mutated giant amino acid aspect chain, which hinders crizotinib from binding to its receptor. Different recognized acquired resistance level mutations embrace p.G1128A, p.1151Tins, p.L1152P/R, p.C1156Y, p.I1171T/N/S, p.F1174V, p.V1180L, p.G1202R, p.S1206Y/C, p.E1210K, and p.G1269A (150–155).

Quite a few research counsel that second-generation medication equivalent to alectinib, ceritinib, brigatinib, and ensatinib could also be more practical than chemotherapy when treating NSCLC sufferers with no response to first-generation ALK inhibitors (64, 156–158). In sufferers handled with second-generation ALK inhibitors, the p.G1202R mutation is the most typical secondary ALK mutation, showing in 21% of ceritinib-treated sufferers, 29% of alectinib-treated sufferers, and 43% of brigatinib-treated sufferers (159).

A acquire in ALK gene fusion copy quantity (greater than two-fold enhance) has lately been proposed as a mechanism of resistance to crizotinib in each in vitro and in sufferers (150, 155). Primarily based on single circulating tumor cell sequencing, one other examine reported repeated mutations within the RTK-KRAS (EGFR, KRAS, BRAF genes), TP53, and different genes within the ALK-independent pathway in crizotinib-resistant sufferers (160).

Resistance to ALK inhibitors can even happen by means of the activation of bypass signaling pathways, together with YAP transcription co-regulator, EGFR signaling, KIT amplification, the IGF-1R pathway, MAPK amplification, the BRAF p.V600E mutation, and MET amplification (155, 161–165). MET amplification was noticed in 15% of tumor samples from sufferers progressing after second-generation ALK inhibitors, and in 12% and 22% of tumor biopsy samples from sufferers progressing on second-generation inhibitors or lorlatinib, respectively (166).

3.4 Resistance to ROS1 inhibitors

Single nucleotide mutations within the ROS1 kinase area, equivalent to p.D2033N, p.G2032R/Okay, p.L2026M, p.L2155S, and p.S1986F/Y, have been reported resulting in acquired resistance to ROS1 TKIs in ROS1 fusion-positive NSCLC by means of preclinical and medical research (167–171). These mutations diminish the efficacy of kinase inhibitors (112, 168, 172).

A examine evaluating biopsies from 55 sufferers progressing after TKI therapy discovered that ROS1 mutations have been recognized in 38% of post-crizotinib biopsies and 46% of post-lorlatinib biopsies. Roughly one-third of sufferers harbored the most typical mutation ROS1 p.G2032R. Extra ROS1 mutations emerged following crizotinib therapy, together with p.D2033N (2.4%), p.S1986F (2.4%), p.L2086F (3.6%), p.G2032R/p.L2086F (3.6%), and p.G2032R/p.S1986F/p.L2086F (3.6%). p.S1986F/p.L2000V (3.6%) was detected in 3.6% of sufferers receiving lorlatinib therapy (170).

The p.D2033N mutation causes the substitution of aspartate for asparagine at place 2033 within the ROS1 kinase hinge area, thus resulting in vital resistance to ROS1 inhibitors in vitro (173, 174). The p.L2026M and p.G2032R mutations within the ROS1 kinase area confer crizotinib resistance by altering the “gatekeeper” place of ROS1 inhibitor binding (168, 175). Moreover, p.S1986F/Y within the kinase area disrupts essential activation websites, thereby growing kinase exercise. p.L2155S is anticipated to confer crizotinib resistance by means of protein dysfunction (176).

The mutations and/or copy quantity will increase of genes in different RTKs or downstream MAPK pathway are additionally concerned within the mechanism of resistance to ROS1 inhibitor (177). Mediators concerned on this pathway embrace KRAS, NRAS, EGFR, HER2, MET, KIT, BRAF, and MEK, both as downstream or bypass mediators (167, 168, 172, 174). KRAS p.G12D and BRAF p.V600E mutations are related to crizotinib therapy, whereas NRAS p.Q61K is related to entrectinib therapy (178).

4 Methods for overcoming resistance to TKIs

Focused therapies have considerably improved the prognosis of NSCLC sufferers with related genetic alterations, which is a significant progress within the historical past of NSCLC therapy. Nonetheless, a part of the sufferers acquires TKI resistance and illness development shortly after preliminary remission. Methods have been investigated to overcoming resistance to TKIs, which embrace the continuation of TKI remedy past illness development, mixture with different TKIs, and the usage of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

4.1 Continuation of TKI remedy past illness development

A section II open-label single-arm trial named ASPIRATION reported that the post-progression erlotinib sufferers exhibited deeper responses, longer PFS, extended time from total response to development, and fewer new lung lesions (179). A retrospective evaluation of 414 ALK-positive NSCLC sufferers enrolled in PROFILE 1001 and PROFILE 1005 confirmed that continuation of crizotinib (>3 weeks) after development conferred prolonged development time and longer OS (180). Nonetheless, extra proof helps the well timed detection of potential resistance mutations and immediate switching to delicate focused therapies after illness development.

4.2 Mixture with different TKIs

In a section Ib/II single-arm trial, 47% of EGFR TKI-resistant NSCLC sufferers with MET gene amplification and 32% of EGFR TKI-resistant sufferers with MET overexpression responded to the MET inhibitor capmatinib together with EGFR TKI (181). In one other section 1b examine of the mixture of the MET inhibitors savolitinib and gefitinib, as much as 52% of sufferers with EGFR TKI-resistant NSCLC with MET gene amplification had an goal response to the mixture therapy routine (182). Within the subsequent INSIGHT examine, 67% of EGFR TKI-resistant NSCLC sufferers with MET gene amplification had an goal therapeutic response to therapy with the MET inhibitor tepotinib mixed with gefitinib (183). And within the section Ib trial of the TATTON examine, 64% of NSCLC sufferers who have been proof against first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs and had MET gene amplification confirmed improved response to savolitinib mixed with osimertinib. Nonetheless, solely 30% of sufferers who have been proof against third-generation EGFR TKIs and had MET gene amplification confirmed an goal response to this mix remedy (184).

4.3 Immune checkpoint inhibitors

In recent times, checkpoint inhibitor antibodies, together with programmed cell demise protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors and programmed demise ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, have demonstrated favorable outcomes in NSCLC therapy by blocking the PD-1 and PD-L1 interplay and enhancing the antitumor results of endogenous T cells. Pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and cemiplimab have all been reported to lengthen PFS and OS in eligible sufferers (185–189). Nonetheless, the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitor antibodies will depend on the expression stage of PD-L1, and for sure mutations equivalent to EGFR exon 19 deletions, EGFR p.L858R mutations, or ALK rearrangements, they seemed to be much less efficient (190–194).

In conclusion, focused remedy has introduced vital advantages to NSCLC sufferers, however the emergence of TKI resistance poses a formidable impediment. The therapy of NSCLC nonetheless has an extended method to go.

Creator contributions

HZ: Writing – authentic draft, Writing – evaluate & modifying. YZhang: Writing – authentic draft, Writing – evaluate & modifying. YZhu: Visualization, Writing – evaluate & modifying. TD: Writing – evaluate & modifying. ZL: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – evaluate & modifying.

Funding

The writer(s) declare monetary assist was acquired for the analysis, authorship, and/or publication of this text. This work was supported by the Science and Know-how Assist Program of Sichuan Province (2023NSFSC0732).

Battle of curiosity

The authors declare that the analysis was carried out within the absence of any business or monetary relationships that may very well be construed as a possible battle of curiosity.

Writer’s word

All claims expressed on this article are solely these of the authors and don’t essentially symbolize these of their affiliated organizations, or these of the writer, the editors and the reviewers. Any product which may be evaluated on this article, or declare which may be made by its producer, will not be assured or endorsed by the writer.

References

1. Planchard D, Besse B, Groen HJM, Hashemi SMS, Mazieres J, Kim TM, et al. Part 2 examine of dabrafenib plus trametinib in sufferers with BRAF V600E-mutant metastatic NSCLC: up to date 5-year survival charges and genomic evaluation. J Thorac Oncol. (2022) 17:103–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.08.011

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

2. Mok T, Camidge DR, Gadgeel SM, Rosell R, Dziadziuszko R, Kim DW, et al. Up to date total survival and closing progression-free survival information for sufferers with treatment-naive superior ALK-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers within the ALEX examine. Ann Oncol. (2020) 31:1056–64. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.478

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

3. Lin JJ, Cardarella S, Lydon CA, Dahlberg SE, Jackman DM, Jänne PA, et al. 5-year survival in EGFR-mutant metastatic lung adenocarcinoma handled with EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol. (2016) 11:556–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.12.103

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

4. Shaw AT, Riely GJ, Bang YJ, Kim DW, Camidge DR, Solomon BJ, et al. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged superior non-small-cell lung most cancers (NSCLC): up to date outcomes, together with total survival, from PROFILE 1001. Ann Oncol. (2019) 30:1121–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz131

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

5. Garon EB, Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, Carcereny E, Leighl NB, Ahn MJ, et al. 5-year total survival for sufferers with superior non−Small-cell lung most cancers handled with pembrolizumab: outcomes from the section I KEYNOTE-001 examine. J Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:2518–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00934

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

6. Singhi EK, Horn L, Sequist LV, Heymach J, Langer CJ. Superior non-small cell lung most cancers: sequencing brokers within the EGFR-mutated/ALK-rearranged populations. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Guide. (2019) 39:e187–97. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_237821

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

7. Antonia SJ, Borghaei H, Ramalingam SS, Horn L, De Castro Carpeño J, Pluzanski A, et al. 4-year survival with nivolumab in sufferers with beforehand handled superior non-small-cell lung most cancers: a pooled evaluation. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:1395–408. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30407-3

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

8. Zhao Y, Wang S, Yang Z, Dong Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, et al. Co-occurring doubtlessly actionable oncogenic drivers in non-small cell lung most cancers. Entrance Oncol. (2021) 11:665484. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.665484

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

9. Graham RP, Treece AL, Lindeman NI, Vasalos P, Shan M, Jennings LJ, et al. Worldwide frequency of generally detected EGFR mutations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2018) 142:163–7. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2016-0579-CP

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

10. Han B, Tjulandin S, Hagiwara Okay, Normanno N, Wulandari L, Laktionov Okay, et al. EGFR mutation prevalence in Asia-Pacific and Russian sufferers with superior NSCLC of adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma histology: The IGNITE examine. Lung Most cancers. (2017) 113:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.08.021

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

11. Harrison PT, Vyse S, Huang PH. Uncommon epidermal development issue receptor (EGFR) mutations in non-small cell lung most cancers. Semin Most cancers Biol. (2020) 61:167–79. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.09.015

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

12. Martinez-Marti A, Navarro A, Felip E. Epidermal development issue receptor first era tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. Transl Lung Most cancers Res. (2019) 8:S235–s246. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.04.20

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

13. Jackman DM, Miller VA, Cioffredi LA, Yeap BY, Jänne PA, Riely GJ, et al. Influence of epidermal development issue receptor and KRAS mutations on medical outcomes in beforehand untreated non-small cell lung most cancers sufferers: outcomes of a web-based tumor registry of medical trials. Clin Most cancers Res. (2009) 15:5267–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0888

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

14. Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, et al. Erlotinib versus customary chemotherapy as first-line therapy for European sufferers with superior EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised section 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2012) 13:239–46. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

15. Jänne PA, Wang X, Socinski MA, Crawford J, Stinchcombe TE, Gu L, et al. Randomized section II trial of erlotinib alone or with carboplatin and paclitaxel in sufferers who have been by no means or gentle former people who smoke with superior lung adenocarcinoma: CALGB 30406 trial. J Clin Oncol. (2012) 30:2063–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.1315

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

16. Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi Okay, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung most cancers with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. (2010) 362:2380–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

17. Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. (2009) 361:947–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

18. Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, Feng J, Liu XQ, Wang C, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line therapy for sufferers with superior EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, section 3 examine. Lancet Oncol. (2011) 12:735–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

19. Urata Y, Katakami N, Morita S, Kaji R, Yoshioka H, Seto T, et al. Randomized section III examine evaluating gefitinib with erlotinib in sufferers with beforehand handled superior lung adenocarcinoma: WJOG 5108L. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:3248–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.4154

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

21. Park Okay, Tan EH, O’Byrne Okay, Zhang L, Boyer M, Mok T, et al. Afatinib versus gefitinib as first-line therapy of sufferers with EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers (LUX-Lung 7): a section 2B, open-label, randomised managed trial. Lancet Oncol. (2016) 17:577–89. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30033-X

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

22. Paz-Ares L, Tan EH, O’Byrne Okay, Zhang L, Hirsh V, Boyer M, et al. Afatinib versus gefitinib in sufferers with EGFR mutation-positive superior non-small-cell lung most cancers: total survival information from the section IIb LUX-Lung 7 trial. Ann Oncol. (2017) 28:270–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw611

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

23. Yang JC, Sequist LV, Geater SL, Tsai CM, Mok TS, Schuler M, et al. Medical exercise of afatinib in sufferers with superior non-small-cell lung most cancers harbouring unusual EGFR mutations: a mixed post-hoc evaluation of LUX-Lung 2, LUX-Lung 3, and LUX-Lung 6. Lancet Oncol. (2015) 16:830–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00026-1

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

24. Wu YL, Cheng Y, Zhou X, Lee KH, Nakagawa Okay, Niho S, et al. Dacomitinib versus gefitinib as first-line therapy for sufferers with EGFR-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers (ARCHER 1050): a randomised, open-label, section 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2017) 18:1454–66. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30608-3

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

25. Mok TS, Cheng Y, Zhou X, Lee KH, Nakagawa Okay, Niho S, et al. Enchancment in total survival in a randomized examine that in contrast dacomitinib with gefitinib in sufferers with superior non-small-cell lung most cancers and EGFR-activating mutations. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:2244–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.7994

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

26. Mok TS, Cheng Y, Zhou X, Lee KH, Nakagawa Okay, Niho S, et al. Up to date total survival in a randomized examine evaluating dacomitinib with gefitinib as first-line therapy in sufferers with superior non-small-cell lung most cancers and EGFR-activating mutations. Medication. (2021) 81:257–66. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01441-6

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

27. Cross DA, Ashton SE, Ghiorghiu S, Eberlein C, Nebhan CA, Spitzler PJ, et al. overcomes T790M-mediated resistance to EGFR inhibitors in lung most cancers. Most cancers Discovery. (2014) 4:1046–61. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0337

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

28. Ballard P, Yates JW, Yang Z, Kim DW, Yang JC, Cantarini M, et al. Preclinical comparability of osimertinib with different EGFR-TKIs in EGFR-mutant NSCLC mind metastases fashions, and early proof of medical mind metastases exercise. Clin Most cancers Res. (2016) 22:5130–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0399

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

29. Yang JC-H, Kim D-W, Kim S-W, Cho BC, Lee J-S, Ye X, et al. Osimertinib exercise in sufferers (pts) with leptomeningeal (LM) illness from non-small cell lung most cancers (NSCLC): Up to date outcomes from BLOOM, a section I examine. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.34.15_suppl.9002

30. Remon J, Steuer CE, Ramalingam SS, Felip E. Osimertinib and different third-generation EGFR TKI in EGFR-mutant NSCLC sufferers. Ann Oncol. (2018) 29:i20–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx704

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

31. Mok TS, Wu YL, Ahn MJ, Garassino MC, Kim HR, Ramalingam SS, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:629–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612674

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

32. Yang JCH, Kim SW, Kim DW, Lee JS, Cho BC, Ahn JS, et al. Osimertinib in sufferers with epidermal development issue receptor mutation-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers and leptomeningeal metastases: the BLOOM examine. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:538–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00457

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

33. Yang JC-H, Cho BC, Kim D-W, Kim S-W, Lee J-S, Su W-C, et al. Osimertinib for sufferers (pts) with leptomeningeal metastases (LM) from EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung most cancers (NSCLC): Up to date outcomes from the BLOOM examine. J Clin Oncol. (2017). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.2020

34. Cho JH, Lim SH, An HJ, Kim KH, Park KU, Kang EJ, et al. Osimertinib for sufferers with non-small-cell lung most cancers harboring unusual EGFR mutations: A multicenter, open-label, section II trial (KCSG-LU15-09). J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:488–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.00931

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

35. Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, Cho BC, Grey JE, Ohe Y, et al. General survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated superior NSCLC. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

36. Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated superior non-small-cell lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:113–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

37. Park Okay, Haura EB, Leighl NB, Mitchell P, Shu CA, Girard N, et al. Amivantamab in EGFR exon 20 insertion-mutated non-small-cell lung most cancers progressing on platinum chemotherapy: preliminary outcomes from the CHRYSALIS section I examine. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39:3391–402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00662

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

38. Zhou C, Tang KJ, Cho BC, Liu B, Paz-Ares L, Cheng S, et al. Amivantamab plus chemotherapy in NSCLC with EGFR exon 20 insertions. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:2039–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2306441

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

39. Passaro A, Wang J, Wang Y, Lee SH, Melosky B, Shih JY, et al. Amivantamab plus chemotherapy with and with out lazertinib in EGFR-mutant superior NSCLC after illness development on osimertinib: major outcomes from the section III MARIPOSA-2 examine. Ann Oncol. (2024) 35:77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.117

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

40. Zhou C, Ramalingam SS, Kim TM, Kim SW, Yang JC, Riely GJ, et al. Therapy outcomes and security of mobocertinib in platinum-pretreated sufferers with EGFR exon 20 insertion-positive metastatic non-small cell lung most cancers: A section 1/2 open-label nonrandomized medical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2021) 7:e214761. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.4761

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

41. Riely GJ, Neal JW, Camidge DR, Spira AI, Piotrowska Z, Costa DB, et al. Exercise and security of mobocertinib (TAK-788) in beforehand handled non-small cell lung most cancers with EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations from a section I/II trial. Most cancers Discovery. (2021) 11:1688–99. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1598

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

42. Janne P, Wang B, Cho B, Zhao J, Li J, Hochmair M, et al. EXCLAIM-2: Part III trial of first-line (1L) mobocertinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in sufferers (pts) with epidermal development issue receptor (EGFR) exon 20 insertion (ex20ins)+ regionally superior/metastatic NSCLC. Ann OF Oncol. (2023) 34:S1663–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.586

43. Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, von Pawel J, Krzakowski M, Ramlau R, et al. Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in sufferers with superior non-small-cell lung most cancers (FLEX): an open-label randomised section III trial. Lancet. (2009) 373:1525–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60569-9

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

44. Kohno T, Nakaoku T, Tsuta Okay, Tsuchihara Okay, Matsumoto S, Yoh Okay, et al. Past ALK-RET, ROS1 and different oncogene fusions in lung most cancers. Transl Lung Most cancers Res. (2015) 4:156–64. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.11.11

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

45. Zhang SS, Nagasaka M, Zhu VW, Ou SI. Going beneath the tip of the iceberg. Figuring out and understanding EML4-ALK variants and TP53 mutations to optimize therapy of ALK fusion constructive (ALK+) NSCLC. Lung Most cancers. (2021) 158:126–36. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.06.012

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

46. Kim D-W, Ahn M-J, Shi Y, De Pas TM, Yang P-C, Riely GJ, et al. Outcomes of a world section II examine with crizotinib in superior ALK-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers (NSCLC). Ann Oncol. (2012) 23:xi32–3. doi: 10.1016/S0923-7534(20)32006-8

47. Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2010) 363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

48. Camidge DR, Bang YJ, Kwak EL, Iafrate AJ, Varella-Garcia M, Fox SB, et al. Exercise and security of crizotinib in sufferers with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers: up to date outcomes from a section 1 examine. Lancet Oncol. (2012) 13:1011–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70344-3

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

49. Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa Okay, Mekhail T, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2014) 371:2167–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

50. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa Okay, Seto T, Crinó L, Ahn MJ, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in superior ALK-positive lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:2385–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

51. Kodama T, Tsukaguchi T, Yoshida M, Kondoh O, Sakamoto H. Selective ALK inhibitor alectinib with potent antitumor exercise in fashions of crizotinib resistance. Most cancers Lett. (2014) 351:215–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.020

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

52. Gadgeel SM, Gandhi L, Riely GJ, Chiappori AA, West HL, Azada MC, et al. Security and exercise of alectinib in opposition to systemic illness and mind metastases in sufferers with crizotinib-resistant ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung most cancers (AF-002JG): outcomes from the dose-finding portion of a section 1/2 examine. Lancet Oncol. (2014) 15:1119–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70362-6

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

53. Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:829–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704795

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

54. Hida T, Nokihara H, Kondo M, Kim YH, Azuma Okay, Seto T, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in sufferers with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers (J-ALEX): an open-label, randomised section 3 trial. Lancet. (2017) 390:29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30565-2

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

55. Ou SH, Ahn JS, De Petris L, Govindan R, Yang JC, Hughes B, et al. Alectinib in crizotinib-refractory ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung most cancers: A section II international examine. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:661–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.9443

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

56. Shaw AT, Gandhi L, Gadgeel S, Riely GJ, Cetnar J, West H, et al. Alectinib in ALK-positive, crizotinib-resistant, non-small-cell lung most cancers: a single-group, multicentre, section 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2016) 17:234–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00488-X

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

57. Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JC, Han JY, Lee JS, et al. Brigatinib versus crizotinib in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2018) 379:2027–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810171

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

58. Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, Yang JCH, Han JY, Hochmair MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus crizotinib in ALK inhibitor-naive superior ALK-positive NSCLC: closing outcomes of section 3 ALTA-1L trial. J Thorac Oncol. (2021) 16:2091–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.07.035

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

59. Kim DW, Tiseo M, Ahn MJ, Reckamp KL, Hansen KH, Kim SW, et al. Brigatinib in sufferers with crizotinib-refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers: A randomized, multicenter section II trial. J Clin Oncol. (2017) 35:2490–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.5904

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

60. Camidge DR, Tiseo M, Ahn M-J, Reckamp Okay, Hansen Okay, Kim S-W, et al. P3. 02a-013 brigatinib in crizotinib-refractory ALK+ NSCLC: central evaluation and updates from ALTA, a pivotal randomized section 2 trial: subject: ALK medical. J Thorac Oncol. (2017) 12:S1167–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.1643

61. Lim SM, Kim HR, Lee JS, Lee KH, Lee YG, Min YJ, et al. Open-label, multicenter, section II examine of ceritinib in sufferers with non-small-cell lung most cancers harboring ROS1 rearrangement. J Clin Oncol. (2017) 35:2613–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3701

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

62. Soria JC, Tan DSW, Chiari R, Wu YL, Paz-Ares L, Wolf J, et al. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in superior ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung most cancers (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, section 3 examine. Lancet. (2017) 389:917–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30123-X

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

63. Crinò L, Ahn MJ, De Marinis F, Groen HJ, Wakelee H, Hida T, et al. Multicenter section II examine of whole-body and intracranial exercise with ceritinib in sufferers with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung most cancers beforehand handled with chemotherapy and crizotinib: outcomes from ASCEND-2. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:2866–73. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.65.5936

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

64. Shaw AT, Kim TM, Crinò L, Gridelli C, Kiura Okay, Liu G, et al. Ceritinib versus chemotherapy in sufferers with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung most cancers beforehand given chemotherapy and crizotinib (ASCEND-5): a randomised, managed, open-label, section 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2017) 18:874–86. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30339-X

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

65. Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Chiari R, Riely GJ, Besse B, Soo RA, et al. Lorlatinib in superior ROS1-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers: a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, section 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2019) 20:1691–701. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30655-2

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

66. Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Felip E, Soo RA, Camidge DR, et al. Lorlatinib in sufferers with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers: outcomes from a world section 2 examine. Lancet Oncol. (2018) 19:1654–67. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30649-1

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

67. Besse B, Solomon BJ, Felip E, Bauer TM, Ou S-HI, Soo RA, et al. Lorlatinib in sufferers (Pts) with beforehand handled ALK+ superior non-small cell lung most cancers (NSCLC): Up to date efficacy and security. J Clin Oncol. (2018). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.9032

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

68. Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Lin CC, Soo RA, et al. ALK resistance mutations and efficacy of lorlatinib in superior anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers. J Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:1370–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02236

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

69. Shaw AT, Bauer TM, de Marinis F, Felip E, Goto Y, Liu G, et al. First-line lorlatinib or crizotinib in superior ALK-positive lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:2018–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027187

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

70. Solomon BJ, Bauer TM, Ignatius Ou SH, Liu G, Hayashi H, Bearz A, et al. Publish hoc evaluation of lorlatinib intracranial efficacy and security in sufferers with ALK-positive superior non-small-cell lung most cancers from the section III CROWN examine. J Clin Oncol. (2022) 40:3593–602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02278

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

71. Baik CS, Myall NJ, Wakelee HA. Focusing on BRAF-mutant non-small cell lung most cancers: from molecular profiling to rationally designed remedy. Oncologist. (2017) 22:786–96. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0458

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

72. Nguyen-Ngoc T, Bouchaab H, Adjei AA, Peters S. BRAF alterations as therapeutic targets in non-small-cell lung most cancers. J Thorac Oncol. (2015) 10:1396–403. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000644

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

74. Litvak AM, Paik PK, Woo KM, Sima CS, Hellmann MD, Arcila ME, et al. Medical traits and course of 63 sufferers with BRAF mutant lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. (2014) 9:1669–74. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000344

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

75. Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, Grazia Sciarrotta M, Guetti L, Chella A, et al. Medical options and end result of sufferers with non-small-cell lung most cancers harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. (2011) 29:3574–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9638

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

76. Planchard D, Smit EF, Groen HJM, Mazieres J, Besse B, Helland Å, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in sufferers with beforehand untreated BRAF(V600E)-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung most cancers: an open-label, section 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2017) 18:1307–16. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30679-4

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

77. O’Leary CG, Andelkovic V, Ladwa R, Pavlakis N, Zhou C, Hirsch F, et al. Focusing on BRAF mutations in non-small cell lung most cancers. Transl Lung Most cancers Res. (2019) 8:1119–24. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.10.22

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

78. Riely GJ, Smit EF, Ahn MJ, Felip E, Ramalingam SS, Tsao A, et al. Open-label examine of encorafenib plus binimetinib in sufferers with BRAF(V600)-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung most cancers. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:3700–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00774

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

79. Li BT, Shen R, Buonocore D, Olah ZT, Ni A, Ginsberg MS, et al. Ado-trastuzumab emtansine for sufferers with HER2-mutant lung cancers: outcomes from a section II basket trial. J Clin Oncol. (2018) 36:2532–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.9777

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

80. Li BT, Shen R, Buonocore D, Olah ZT, Ni A, Ginsberg MS, et al. Ado-trastuzumab emtansine in sufferers with HER2 mutant lung cancers: Outcomes from a section II basket trial. J Clin Oncol. (2017). doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.8510

81. Iwama E, Zenke Y, Sugawara S, Daga H, Morise M, Yanagitani N, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for sufferers with non-small cell lung most cancers constructive for human epidermal development issue receptor 2 exon-20 insertion mutations. Eur J Most cancers. (2022) 162:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.11.021

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

82. Li BT, Smit EF, Goto Y, Nakagawa Okay, Udagawa H, Mazières J, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in HER2-mutant non-small-cell lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:241–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112431

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

83. Tsurutani J, Iwata H, Krop I, Jänne PA, Doi T, Takahashi S, et al. Focusing on HER2 with trastuzumab deruxtecan: A dose-expansion, section I examine in a number of superior stable tumors. Most cancers Discovery. (2020) 10:688–701. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1014

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

85. Dogan S, Shen R, Ang DC, Johnson ML, D’Angelo SP, Paik PK, et al. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas: increased susceptibility of ladies to smoking-related KRAS-mutant cancers. Clin Most cancers Res. (2012) 18:6169–77. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3265

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

86. Canon J, Rex Okay, Saiki AY, Mohr C, Cooke Okay, Bagal D, et al. The medical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. (2019) 575:217–23. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

87. Nakajima EC, Drezner N, Li X, Mishra-Kalyani PS, Liu Y, Zhao H, et al. FDA approval abstract: sotorasib for KRAS G12C-mutated metastatic NSCLC. Clin Most cancers Res. (2022) 28:1482–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3074

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

88. Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Value TJ, Falchook GS, Wolf J, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:2371–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103695

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

89. de Langen AJ, Johnson ML, Mazieres J, Dingemans AC, Mountzios G, Pless M, et al. Sotorasib versus docetaxel for beforehand handled non-small-cell lung most cancers with KRAS(G12C) mutation: a randomised, open-label, section 3 trial. Lancet. (2023) 401:733–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00221-0

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

90. Jänne PA, Riely GJ, Gadgeel SM, Heist RS, Ou SI, Pacheco JM, et al. Adagrasib in non-small-cell lung most cancers harboring a KRAS(G12C) mutation. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387:120–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

91. Wolf J, Seto T, Han JY, Reguart N, Garon EB, Groen HJM, et al. Capmatinib in MET exon 14-mutated or MET-amplified non-small-cell lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:944–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002787

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

92. Garon EB, Heist RS, Seto T, Han J-Y, Reguart N, Groen HJ, et al. Summary CT082: Capmatinib in MET ex14-mutated (mut) superior non-small cell lung most cancers (NSCLC): Outcomes from the section II GEOMETRY mono-1 examine, together with efficacy in sufferers (pts) with mind metastases (BM). Most cancers Res. (2020) 80:CT082–2. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2020-CT082

93. Choi W, Park SY, Lee Y, Lim KY, Park M, Lee GK, et al. The medical influence of capmatinib within the therapy of superior non-small cell lung most cancers with MET exon 14 skipping mutation or gene amplification. Most cancers Res Deal with. (2021) 53:1024–32. doi: 10.4143/crt.2020.1331

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

94. Drilon A, Clark JW, Weiss J, Ou SI, Camidge DR, Solomon BJ, et al. Antitumor exercise of crizotinib in lung cancers harboring a MET exon 14 alteration. Nat Med. (2020) 26:47–51. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0716-8

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

95. Camidge DR, Otterson GA, Clark JW, Ignatius Ou SH, Weiss J, Ades S, et al. Crizotinib in sufferers with MET-amplified NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. (2021) 16:1017–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.02.010

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

96. Paik PK, Felip E, Veillon R, Sakai H, Cortot AB, Garassino MC, et al. Tepotinib in non-small-cell lung most cancers with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:931–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004407

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

97. Le X, Paz-Ares LG, Van Meerbeeck J, Viteri S, Galvez CC, Smit EF, et al. Tepotinib in sufferers with non-small cell lung most cancers with high-level MET amplification detected by liquid biopsy: VISION Cohort B. Cell Rep Med. (2023) 4:101280. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101280

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

98. Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, DuBois SG, Lassen UN, Demetri GD, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and kids. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:731–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

99. Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, Siena S, Shaw AT, Farago AF, et al. Entrectinib in sufferers with superior or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive stable tumours: built-in evaluation of three section 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. (2020) 21:271–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

100. Drilon A, Barlesi F, Braud FD, Cho BC, Ahn M-J, Siena S, et al. Summary CT192: Entrectinib in regionally superior or metastatic ROS1 fusion-positive non-small cell lung most cancers (NSCLC): Built-in evaluation of ALKA-372-001, STARTRK-1 and STARTRK-2. Most cancers Res. (2019) 79:CT192–2. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2019-CT192

101. Doebele R, Ahn M, Siena S, Drilon A, Krebs M, Lin C, et al. OA02. 01 Efficacy and security of entrectinib in regionally superior or metastatic ROS1 fusion-positive non-small cell lung most cancers (NSCLC). J Thorac Oncol. (2018) 13:S321–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.239

102. Lassen U, Albert CM, Kummar S, Van Tilburg C, DuBois SG, Geoerger B, et al. Larotrectinib efficacy and security in TRK fusion most cancers: an expanded medical dataset displaying consistency in an age and tumor agnostic strategy. Ann Oncol. (2018) 29:viii133. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy279.397

103. Collisson EA, Campbell JD, Brooks AN, Berger AH, Lee W, Chmielecki J, et al. Complete molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. (2014) 511:543–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13385

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

104. Bronte G, Ulivi P, Verlicchi A, Cravero P, Delmonte A, Crinò L. Focusing on RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung most cancers: future prospects. Lung Most cancers (Auckl). (2019) 10:27–36. doi: 10.2147/LCTT

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

105. Gainor JF, Curigliano G, Kim DW, Lee DH, Besse B, Baik CS, et al. Pralsetinib for RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers (ARROW): a multi-cohort, open-label, section 1/2 examine. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:959–69. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00247-3

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

106. Wright KM. FDA approves pralsetinib for therapy of adults with metastatic RET fusion-positive NSCLC. Oncol (Williston Park). (2020) 34:406–6. doi: 10.46883/ONCOLOGY

107. Drilon A, Oxnard GR, Tan DSW, Loong HHF, Johnson M, Gainor J, et al. Efficacy of selpercatinib in RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung most cancers. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:813–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005653

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

108. Drilon A, Oxnard G, Wirth L, Besse B, Gautschi O, Tan S, et al. PL02. 08 registrational outcomes of LIBRETTO-001: a section 1/2 trial of LOXO-292 in sufferers with RET fusion-positive lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. (2019) 14:S6–7.

109. Drilon A, Rekhtman N, Arcila M, Wang L, Ni A, Albano M, et al. Cabozantinib in sufferers with superior RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung most cancers: an open-label, single-centre, section 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. (2016) 17:1653–60. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30562-9

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

110. Drilon A, Wang L, Hasanovic A, Suehara Y, Lipson D, Stephens P, et al. Response to Cabozantinib in sufferers with RET fusion-positive lung adenocarcinomas. Most cancers Discovery. (2013) 3:630–5. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0035

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

112. Dziadziuszko R, Le AT, Wrona A, Jassem J, Camidge DR, Varella-Garcia M, et al. An activating KIT mutation induces crizotinib resistance in ROS1-positive lung most cancers. J Thorac Oncol. (2016) 11:1273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.04.001

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar