1 Introduction

Prostate carcinoma (PCa) is the commonest most cancers in males with out healing remedy for metastatic illness, though various therapeutic methods have contributed to extended survival and decreased therapy-induced issues (1–3). The chemotherapeutic agent docetaxel (DX) is likely one of the best medicine used to deal with metastatic PCa (4). Nevertheless, the efficacy of the DX-based remedy is proscribed to only some months, resulting from remedy resistance (5–7). The sequential remedy with second-line therapeutics stays much less efficient (8). Because of current and rising resistance to DX, modern therapeutic approaches are important in bringing new efficient remedy choices to sufferers with castration- and chemotherapy-resistant PCa.

Previously many years, the demand for complementary and different drugs (CAM) has elevated and is mirrored by its use amongst most cancers sufferers, starting from 30 – 90%, relying on the nation, tradition, most cancers kind and stage (9–11). Like pharmacological brokers, mixture remedy with pure compounds requires thorough investigation to extend efficacy whereas minimizing uncomfortable side effects. Since legitimate scientific investigation concerning the anti-tumor exercise of pure compounds is incessantly missing, contraindications to their use can’t be dominated out (12, 13).

Artemisinin, extracted from Artemisia annua (Candy Wormwood), was developed in Conventional Chinese language Medication to deal with malaria (14). Artesunate (ART) (Determine 1A), derived from artemisinin, displays outstanding anti-cancer exercise in direction of a broad number of tumor cell traces (15, 16), together with prostate carcinoma (17–19). Furthermore, ART displays anti-inflammatory properties, thereby stopping tissue destruction induced by carcinogens in vivo (20). An endoperoxide moiety of ART reacts with iron, resulting in the formation of cytotoxic radicals (21). Most cancers cells have elevated iron and transferrin receptor ranges, in comparison with regular cells, thus, making them inclined to reactive oxygen species (ROS) (22–24). In doxorubicin-resistant T-cell leukemia and cisplatin-resistant neuroblastoma, ART has been proven to set off ROS formation, leading to apoptosis induction (25, 26). ART has additionally brought about cell cycle arrest in ovarian most cancers cells through elevated ROS era (27). Apart from initiating apoptotic cell demise, ART induces ferroptosis, an iron-dependent programmed cell demise in head and neck most cancers (28). The ensuing ART-mediated lower in mobile glutathione (GSH) and accumulation of lipid ROS ranges abrogated cisplatin resistance in these cells. As well as, ART prompts ferroptosis in pancreatic carcinoma cells bearing oncogenic Ras (29). The anti-cancer exercise of ART is due to this fact multifaceted. The objective of the current examine was to research ART’s mode of motion in a panel of therapy-sensitive (parental) and DX-resistant prostate most cancers cells.

Determine 1 Chemical construction of ART (A) and cell progress of regular (wholesome) TEC cells (B) as effectively asof parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) DU145 (C, D), PC3 (E, F), and LNCaP (G, H) PCa cells after 24, 48, and 72 h incubation with ART concentrations ascending from 1 – 100 µM. Untreated cells served as controls. Cell quantity was set to 100% after 24 h incubation. Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Important distinction to untreated management: *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001. n = 3.

2 Supplies and Strategies

2.1 Isolation and Cultivation of Main Human Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells

Main human renal tubular epithelial cells (TEC) served as ‘regular, non-cancerous’ management cells. TEC have been separated, cultured and characterised as described beforehand (30, 31). Briefly, cells have been remoted after tumor nephrectomies from renal tissue not concerned in renal cell carcinoma. The donors gave written knowledgeable consent. Moral requirements have been complied with as outlined by the World Medical Affiliation Declaration of Helsinki. The tissue was disintegrated utilizing crossed blades, digested with collagenase/dispase, and handed via a 106 µm mesh. Remaining cohered cells have been then incubated with collagenase IV, DNase and MgCl2 and additional purified by Percoll density gradient centrifugation (31). After centrifugation, the fraction between 1.05 and 1.076 g/ml was collected and washed twice in three volumes of ice chilly HBSS (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany). Remoted cells have been seeded in 6-well plates. Medium 199 (M4530, Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) with a physiologic glucose focus (100 mg/dl) was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), used as commonplace tradition medium and changed each three to 4 days. Confluent cells have been passaged by trypsinization. Cells between passages 2 and 5 have been used for the experiments.

2.2 Cell Strains

The PCa cell traces DU145, PC3, and LNCaP have been bought from the German Assortment of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ). The DX-resistant sublines have been derived from the Resistant Most cancers Cell Line (RCCL) assortment (http://analysis.kent.ac.uk/industrial-biotechnology-centre/the-resistant-cancer-cell-line-rccl-collection/). Drug-adapted most cancers sublines have been established by steady publicity to stepwise growing drug concentrations as beforehand described (32, 33). DX-sensitive (parental) DU145, PC3, and their respective DX-resistant sublines have been cultivated in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany). Parental LNCaP and the DX-resistant subline have been sub-cultured in Iscove Basal medium (Biochrom GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Media have been supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany), 1% glutamax (Gibco®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany), and 1% Anti/Anti (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany). 20 mM HEPES-buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to the RPMI-1640 medium. The DX-resistant sublines have been uncovered to 12.5 nM DX (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) 3 times every week. All cell traces have been cultivated in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator.

2.3 Drug Therapy

ART (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), dissolved in DMSO, was utilized for twenty-four, 48, or 72 h at a focus of 1-100 μM. Controls (parental and cisplatin-resistant) remained ART-untreated. To judge poisonous results of ART, cell viability was decided by trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). Ferrostatin-1 (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), the ferroptosis inhibitor, was used at a focus of 20 μM.

2.4 Cell Progress and Proliferation

Cell progress was outlined utilizing 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol- 2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) dye. PCa DX-sensitive and DX-resistant cells (50 µL, 1 × 105 cells/mL) have been seeded into 96-well-plates. ART (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was utilized for twenty-four, 48, and 72 h at a focus of 1-100 µM. Then, MTT (0.5 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was added. After 4 h incubation with MTT, cells have been lysed with 100 µL solubilization buffer per effectively containing 10% SDS in 0.01 M HCl. The plates have been then incubated in a single day at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Absorbance at 570 nm was decided for every effectively utilizing a multi-mode microplate-reader (Tecan, Spark 10 M, Crailsheim, Germany). After subtracting background absorbance and offsetting with a normal curve, outcomes have been expressed as imply cell quantity in %. For instance dose-response kinetics, the imply cell quantity after 24 h incubation was set to 100%. Every experiment was achieved in triplicate.

Cell proliferation was measured utilizing a BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine/5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine) cell proliferation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) equipment (Calbiochem/Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany). Cells (50 µL, 1 × 105 cells/mL) have been seeded into 96-well-plates and incubated with ART for 48 h at concentrations from 12.5 to 100 µM. 20 µL BrdU-labeling answer per effectively was added 24 h previous to fixation and marking utilizing anti-BrdU mAb, based on the producer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm utilizing a multi-mode microplate-reader (Tecan, Spark 10 M, Crailsheim, Germany). Values offered as proportion in comparison with untreated controls have been set to 100%.

2.5 Cell Cycle Evaluation

To research cell cycle development of ART-treated and management PCa cells, 1 × 106 cells have been stained with propidium iodide (PI) (50 µg/mL) (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany) and analyzed by move cytometry (Fortessa X20, BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Knowledge acquisition was carried out utilizing DIVA software program (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany), and cell cycle part distribution was analyzed by ModFit LT 5.0 software program (Verity Software program Home, Topsham, ME, USA). The variety of cells within the G0/G1, S, or G2/M phases was expressed as a proportion.

2.6 Cell Demise (Apoptosis, Necrosis, Ferroptosis)

The FITC-Annexin V Apoptosis Detection equipment (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) was used to quantify apoptotic and necrotic occasions. After washing cells twice with PBS, 1 × 105 cells have been resuspended in 500 µL of 1 × binding buffer and incubated with 5 µL Annexin V-FITC and/or 5 µL PI in the dead of night for 15 min. Staining was measured by move cytometer (Fortessa X20, BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). The share of apoptotic and necrotic cells was calculated utilizing DIVA software program (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Additional evaluation was achieved by FlowJo software program (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany).

To judge ferroptosis, cells have been handled with 37.5 µM ART or ART mixed with the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 [20 µM] (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) for twenty-four and 48 h. Ferroptosis was assessed utilizing BrdU cell proliferation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) equipment (Calbiochem/Merck Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany), as described above. For extra particulars, see Cell Progress and Proliferation (2.4).

2.7 Western Blot Evaluation of Cell Cycle and Cell Demise Regulating Proteins

The expression and exercise of cell cycle and cell demise regulating proteins have been explored by Western blot evaluation. Tumor cell lysates (50 µg) have been utilized to 10 or 12% polyacrylamide gel and separated for 10 min at 80 V and 1 h at 120 V. The protein was then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (1 h, 100 V). After blocking with 10% non-fat dry milk for 1 h, the membranes have been incubated in a single day with the next major antibodies directed in opposition to cell cycle regulating proteins: CDK1 (Mouse IgG1, clone 2), CDK2 (Mouse IgG2a, clone 55), cyclin A (Mouse IgG1, clone 25), cyclin B (Mouse IgG1, clone 18), and cyclin D1 (Rabbit IgG, clone 92G2), (all: BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany).

To point apoptosis and ferroptosis-related proteins, the next major antibodies in opposition to the corresponding proteins (whole expression) have been used: caspase 3 (Rabbit, pAb), caspase 8 (Rabbit IgG, clone D35G2), PARP-1 (Rabbit IgG, clone 46D11), (all Cell Signaling, Frankfurt am Foremost, Germany), and GPX4 (Rabbit IgG, ab41787, Abcam, Berlin, Germany). HRP-conjugated rabbit-anti-mouse IgG or goat-anti-rabbit IgG served as secondary antibodies (IgG, each: dilution 1:1000, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). The membranes have been incubated 2 min with an ECL detection reagent (AC2204, Azure Biosystems, Munich, Germany) to visualise proteins with a Sapphire Imager (Azure Biosystems, Munich, Germany). Protein expression was normalized to whole protein. To quantify whole protein all membranes have been stained with Coomassie sensible blue and measured by Sapphire Imager. AlphaView software program (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA) was used for pixel density evaluation of the protein bands. The ratio of protein depth/β-actin depth or entire protein depth was calculated and expressed in proportion, associated to the untreated management, set to 100%.

2.8 GSH Assay

The GSH degree was evaluated utilizing the GSH-Glo™ Glutathione Assay (Promega GmbH, Walldorf, Germany). 5 × 103 cells/effectively have been seeded right into a 96-well plate and incubated for twenty-four h with 37.5 µM ART. Experiments have been carried out based on the producer’s protocol. Luminescence was measured utilizing a multi-mode microplate-reader (Tecan, Spark 10 M, Tecan, Grödig, Austria).

2.9 Statistical Evaluation

All experiments have been carried out not less than 3 times. The analysis and era of imply values in addition to normalization in % have been achieved with Microsoft Excel. The usual deviation and statistical significance was calculated with GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software program Inc., San Diego, CA, USA): two-sided t-Check (Western blot, apoptosis, cell cycle), one-way ANOVA check (BrdU), and two-way ANOVA check (MTT). Correction for a number of comparisons was achieved utilizing the conservative Bonferroni technique. Variations have been thought-about statistically important at a p-value ≤.05.

3 Outcomes

3.1 ART Inhibits Cell Progress and Proliferation of Parental and DX-Resistant PCa Cells

Tumor cell progress and proliferation of parental and DX-resistant PCa cells in addition to of ‘regular/non-tumor’ cells have been evaluated after ART software. Progress of ART-treated ‘regular’ cells, right here major human renal tubular epithelial cells (TEC), remained unchanged, in comparison with the untreated cells (Determine 1B). In distinction, ART induced a big time- and dose-dependent progress inhibition in parental and DX-resistant DU145, PC3, and LNCaP cells (Figures 1C–H). Parental and DX-resistant DU145 and LNCaP cells confirmed comparable progress inhibitory results after 72 h publicity to ART (Figures 1C, D, G, H). In distinction, DX-resistant PC3 cells responded extra sensitively to ART than their parental counterparts (Figures 1E, F). Each parental and DX-resistant DU145 cells revealed first important progress inhibition after 72 h at an ART focus of 5 µM (Figures 1C, D). Parental PC3 cells additionally confirmed progress inhibition at 5 µM ART. DX-resistant PC3 cells first displayed progress inhibition at 10 µM ART, however confirmed a complete response, leaving no extra cells on the highest focus of 100 µM (Determine 1F). In parental PC3 cells, 100 µM ART induced a lower in cell quantity however didn’t result in the demise of all cells (Determine 1E), as seen with the DX-resistant PC3 cells (Determine 1F). LNCaP cells, each parental and DX-resistant, responded with a big discount of tumor cell progress at 20 µM ART. Since remedy with 37.5 µM confirmed a robust progress inhibitory impact in all examined cell traces, 37.5 µM ART and better concentrations have been used within the following experiments.

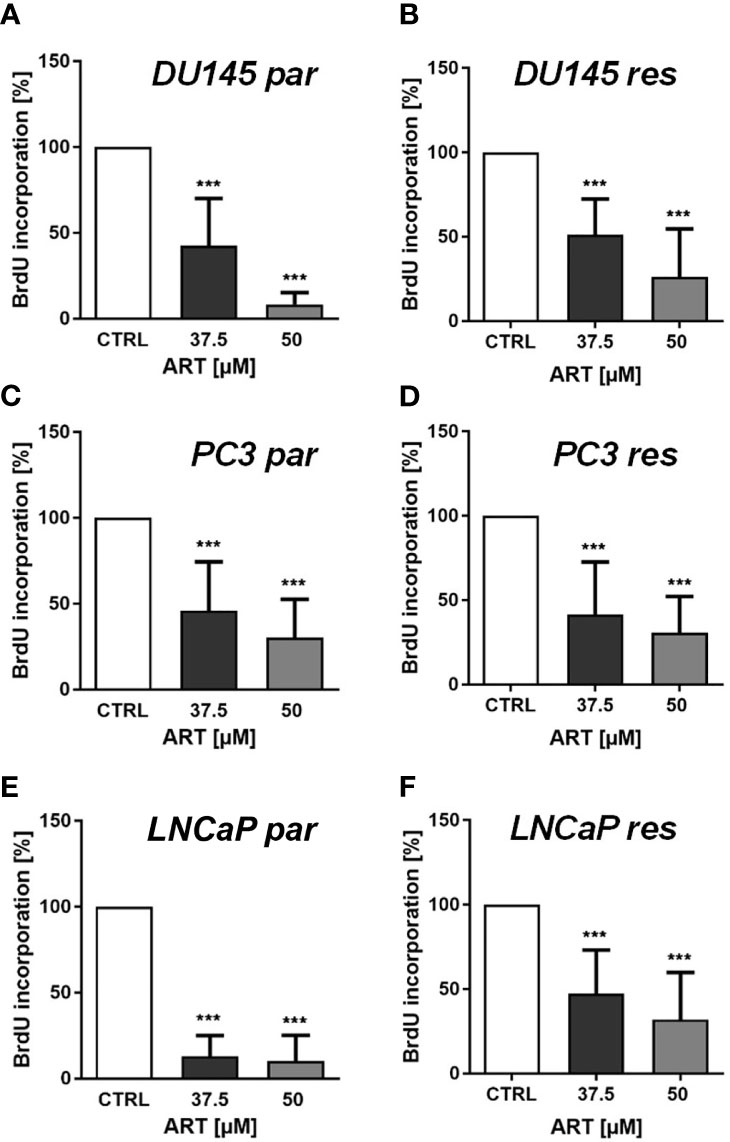

Consistent with the expansion knowledge, proliferation of all parental and DX-resistant PCa cells was considerably diminished in a dose-dependent method after publicity to ART for 48 h (Figures 2A–F).

Determine 2 Tumor cell proliferation of parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) DU145 (A, B), PC3 (C, D), and LNCaP (E, F) cells incubated for 48 h with ART [37.5 and 50 µM]. Untreated controls have been set to 100%. Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Important distinction to untreated management: ***p ≤ .001. n = 3.

3.2 ART Induces Cell Cycle Arrest, Accompanied by Alterations within the Expression of Cell Cycle Regulating Proteins

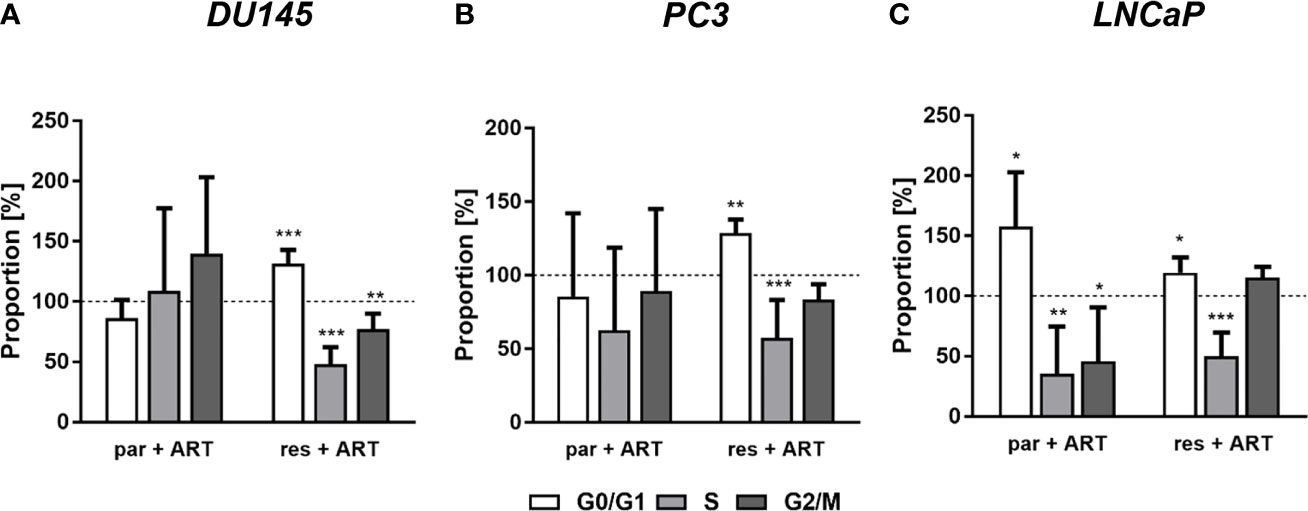

In parental and DX-resistant PCa cells, ART-mediated cell progress inhibition and decreased proliferation have been related to impaired cell cycle development. ART brought about a big G0/G1 part arrest in DX-resistant DU145, PC3, and LNCaP cells (Figures 3A–C). The rise in G0/G1 part was related with a big discount in S part (all) and G2/M part (DU145) cells (Figures 3A–C). Moreover, ART resulted in a big achieve of G0/G1 part cells and a simultaneous lower of S and G2/M part cells in parental LNCaP cells (Determine 1C). In distinction, parental DU145 and PC3 cells confirmed no important modifications in cell cycle development after remedy with ART (Figures 3A, B).

Determine 3 Distribution of cell cycle phases: proportion of parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) PCa cells, DU145 (A), PC3 (B), and LNCaP (C), within the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases after 48 h ART software [37.5 µM]. Untreated cells served as controls (dotted line set to 100%). Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Important distinction to untreated management: *p ≤.05, **p ≤.01, ***p ≤.001. n = 3.

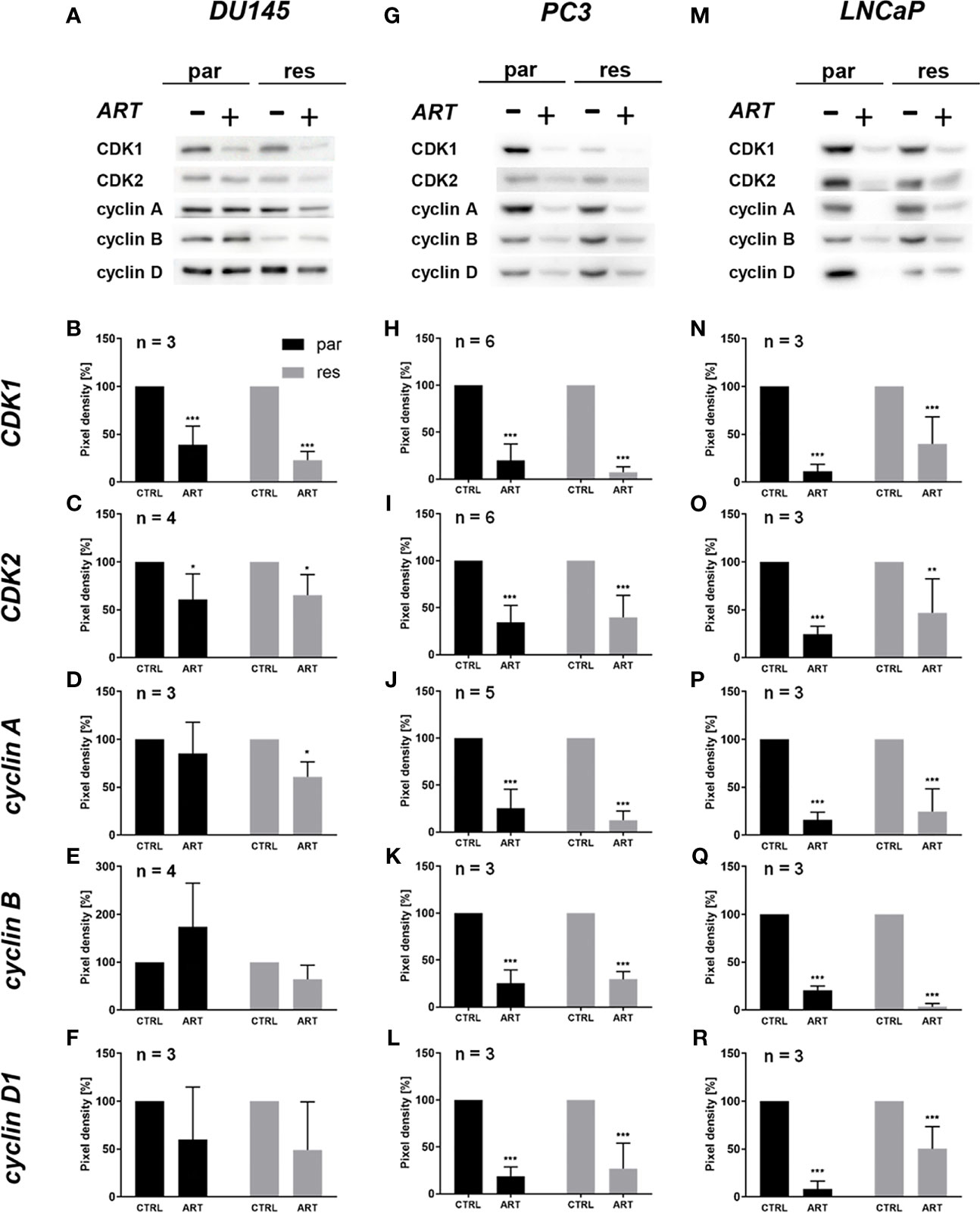

The G0/G1 cell cycle arrest within the PCa cells was accompanied by considerably diminished expression of regulating CDK-cyclin complexes (Determine 4). In DX-resistant DU145, DX-resistant PC3, and each parental and DX-resistant LNCaP cells, the cell cycle proteins answerable for profitable S and G2/M part development, CDK1 (Figures 4A, B, G, H, M, N and Determine S1.1, 1.6, 1.11) and CDK2 (Figures 4A, C, G, I, M, O and Determine S1.2, 1.7, 1.12), in addition to cyclin A (Figures 4A, D, G, J, M, P and Determine S1.3, 1.8, 1.13) have been considerably down-regulated in response to ART. Furthermore, DX-resistant PC3 and parental and DX-resistant LNCaP cells revealed a big lower of cyclin B (Figures 4G, Ok, M, Q and Determine S1.9, 1.14), concerned in G2/M part development, and cyclin D1 (Figures 4G, L, M, R and Determine S1.10, 1.15), answerable for G0/G1 part development. Additionally within the parental DU145 and PC3 cells expression of some activating proteins have been impaired, nonetheless with out affecting cell cycle regulation.

Determine 4 Expression of cell cycle regulating proteins: consultant Western blot pictures of cell cycle regulating proteins in parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) DU145 (A), PC3 (G), and LNCaP (M) cells with (+) and with out (-) ART. Pixel density evaluation of the expression of cell cycle regu-lating proteins CDK1 (B, H, N), CDK2 (C, I, O), cyclin A (D, J, P), cyclin B (E, Ok, Q) and cyclin D1 (F, L, R) in parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) cells after 48 h publicity to ART [37.5 µM], in comparison with untreated controls (set to 100%). Evaluation of pixel density was normalized by a complete protein staining. Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Important distinction to untreated management: *p ≤.05, **p ≤.01, ***p ≤.001. n = 3. For detailed data concerning the Western blots, see Figures S1.1–15.

3.3 Artesunate Induces Apoptotic Cell Demise in PCa Cells

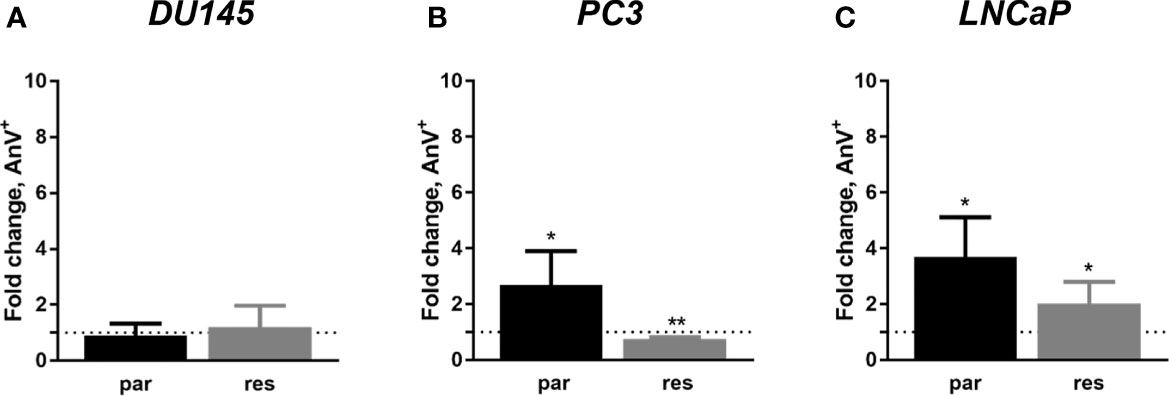

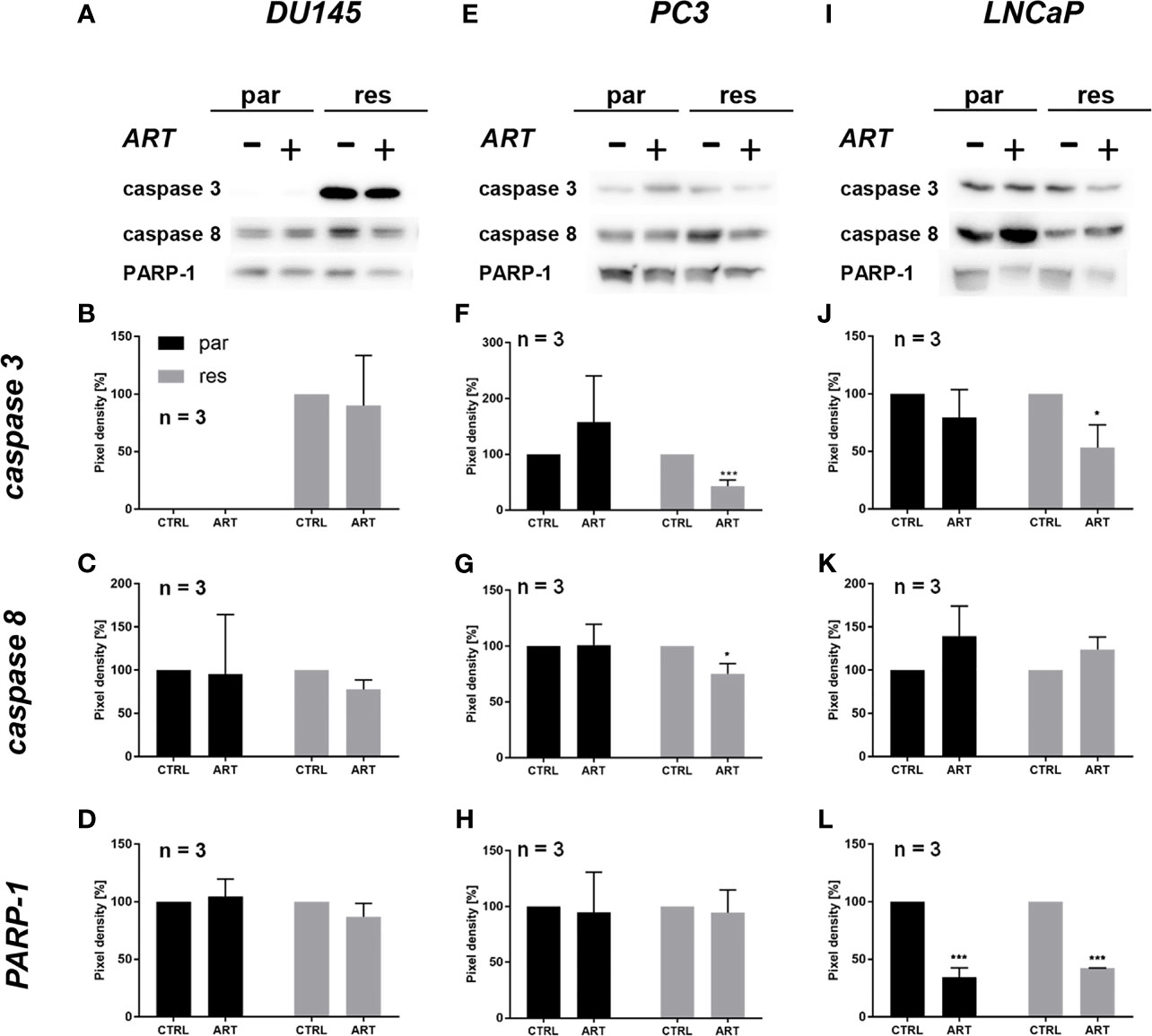

Since modifications in cell cycle development after ART remedy couldn’t clarify the noticed progress and proliferation inhibition in all three PCa cell traces, apoptosis was assessed. No apoptotic occasions have been detected after publicity to ART in parental and DX-resistant DU145 cells, in comparison with the untreated management (Determine 5A). This was verified by no important alteration within the expression of PARP-1 and effector caspases 3 and eight (Figures 6A–D and Determine S2.1–3). A big elevation of apoptotic cells was detected in parental PC3 cells (Determine 5B) despite the fact that no important modifications have been detected within the chosen proteins answerable for apoptotic signaling (Figures 6E–H and Determine S2.4–6). A rise in apoptotic occasions was noticed in each parental and DX-resistant LNCaP cells (Determine 5C). Right here, activated apoptotic signaling was confirmed by a big down-regulation of caspase 3 in DX-resistant LNCaP cells and PARP-1 in each parental and DX-resistant LNCaP cells after publicity to ART (Figures 6I–L and Determine S2.7–9). Necrotic occasions have been typically low and remained unchanged after ART remedy (knowledge not proven).

Determine 5 Apoptosis induction: parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) DU145 (A), PC3 (B), and LNCaP (C) cells handled for 48 h with ART [37.5 µM]. The evaluation was carried out by Annexin V (AnV+)/PI detection (in fold change). Untreated cells served as controls (dotted line, set to 1). Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Important distinction to untreated management: *p ≤.05, **p ≤.01. n = 3.

Determine 6 Apoptotic signaling: consultant Western blot pictures of apoptosis-related proteins in parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) DU145 (A), PC3 (E) and LNCaP (I) cells with (+) and with out (-) ART. Pixel density of caspase 3 (B, F, J), caspase 8 (C, G, Ok) and PARP-1 (D, H, L) expression in parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) cells. All protein evaluation was normalized by a complete protein management. Untreated cells served as controls (100%). Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Important distinction indicated by: *p ≤ .05, ***p ≤ .001. n = 3. For detailed data concerning the Western blots, see Figures S2.1–9.

3.4 Artesunate Induces Ferroptosis in DU145 However Not in PC3 or LNCaP Cells

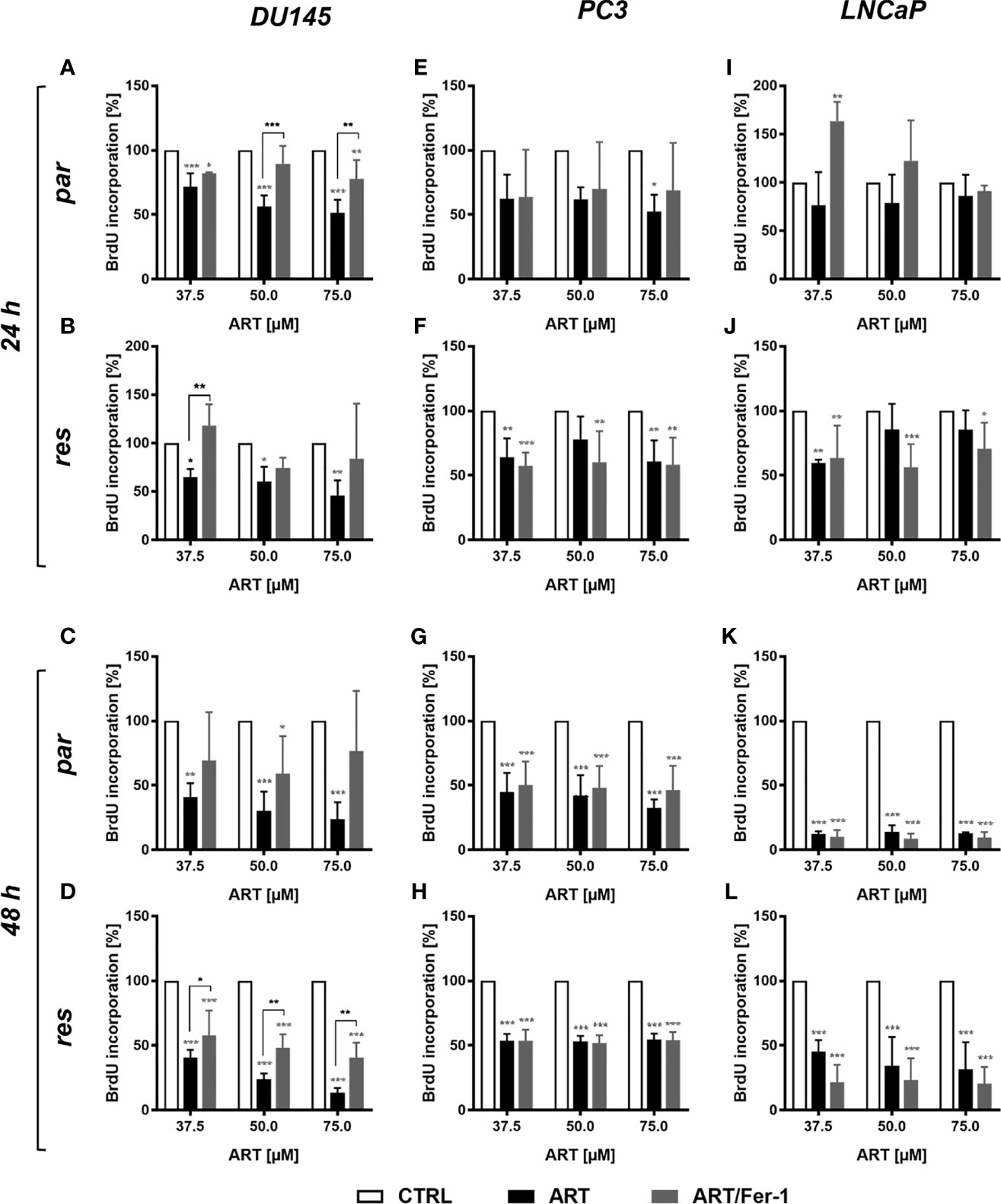

Neither cell cycle development nor apoptosis was induced within the parental DU145 cells after ART remedy and will clarify the noticed progress and proliferation inhibition. Since ART has been proven to activate ferroptosis, an alternate iron-dependent cell demise (29, 34, 35), ferroptosis was investigated. Mixed software of ART with ferrostatin-1, a ferroptosis inhibitor, considerably counteracted ART’s inhibitory impact on proliferation in parental DU145 cells after 24 h (Determine 7A). This impact signifies that ferroptosis induction in parental DU145 cells contributes to the ART-mediated proliferation block. Additionally, in DX-resistant DU145 cells ferrostatin-1 software confirmed important abrogation of ART’s [37.5 µM] anti-proliferative exercise after 24 h, though to a decrease extent (Determine 7B). The counteracting impact of ferrostatin-1 within the DX-resistant cells additional elevated after 48 h (Determine 7D), demonstrating a later activation of ferroptosis in DX-resistant DU145 cells. In distinction, within the parental DU145 cells the proliferation inhibition by ART was now not considerably impaired, when mixed with ferrostatin-1 for 48 h (Determine 7C), additional corroborating the time-shift in ferroptosis-activation in parental and DX-resistant DU145 cells.

Determine 7 Ferroptosis induction: cell proliferation of parental (par) and DX-resistant (res) DU145, PC3, and LNCaP cells handled for twenty-four (A, B, E, F, I, J) and 48 h (C, D, G, H, Ok, L) with ART [37.5 – 75 µM], alone or together with ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) [20 µM]. Untreated cells (100%) served as controls. Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Asterisk brackets point out important distinction between ART and ART with ferrostatin-1 remedy. Important distinction in comparison with untreated controls indicated by: *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001. n = 3.

Nevertheless, in parental and DX-resistant PC3 cells, mixed ART software with ferrostatin-1 didn’t have an effect on the efficacy of ART’s anti-proliferative exercise (Figures 7E–H). Additionally in parental or DX-resistant LNCaP cells, additive administration of ferrostain-1 had no consequence on the ART-induced discount of proliferation (Figures 7I–L). Thus, ART induces ferroptosis solely in parental and DX-resistant DU145 cells. Due to this fact, solely in these cell traces was the influence of ART on ROS manufacturing studied.

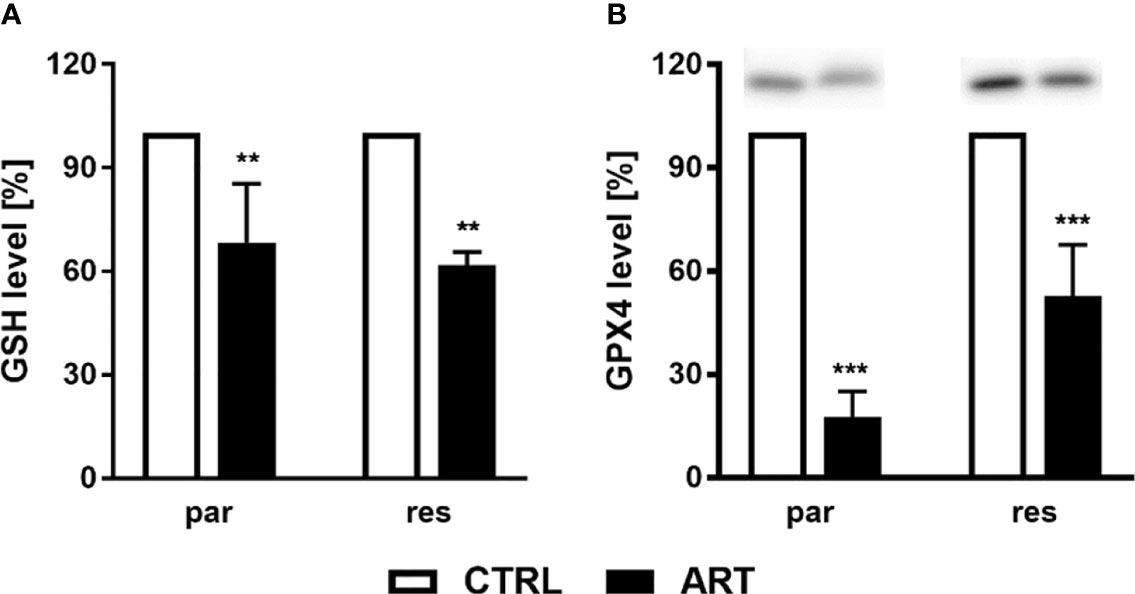

To research whether or not ART remedy ends in ROS era, the content material of glutathione (GSH) and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), elements of the antioxidant safety mechanism, have been decided in ART-treated PCa cells. Biochemically, ferroptosis is characterised by consumption of extracellular GSH and decreased GPX4 ranges. Thereby, discount of GPX4 ranges results in intracellular accumulation of ROS, triggering ferroptosis. Administration of ART in parental and DX-resistant DU145 cells considerably decreased intracellular GSH content material, in comparison with untreated controls, indicating increased GSH consumption and ROS era (Determine 8A). Furthermore, expression of GPX4 was considerably diminished in parental DU145 cells by 37.5 μM ART (Determine 8B and Determine S3). Important down-regulation of GPX4 expression by ART was additionally noticed in DX-resistant DU145 cells, albeit to a lesser extent than within the parental counterpart (Determine 8B and Determine S3).

Determine 8 ROS manufacturing: GSH degree [%] of DU145 cells after 24 h incubation with ART [37.5 µM], in comparison with untreated controls (set to 100%) (A). n = 3. Pixel density evaluation of the GPX4 expression after publicity to ART [37.5 µM] (B). Error bars point out commonplace deviation (SD). Important distinction to untreated controls indicated by: **p ≤.01, ***p ≤.001. n = 3. For detailed data concerning the Western blots, see Determine S3.

4 Dialogue

Regardless of latest progress, PCa stays a problem with out healing remedy for metastatic illness. Therefore, the will for complementary and different drugs (CAM) has gained widespread curiosity previously many years. Nevertheless, science-based data regarding the anti-tumor properties of CAM remains to be restricted. Due to this fact, the current examine was designed to guage the therapeutic potential of ART in parental and DX-resistant PCa cell traces. Per earlier findings in therapy-sensitive PCa cells DU145, LNCaP (36), and 22rvl (19), a potent and dose-dependent inhibition of cell progress and proliferation by ART was noticed. The ART concentrations affecting PCa cells in vitro are clinically related, since ART attaining these concentrations has been utilized to deal with sufferers with refractory stable tumors (37) and malaria (38). Apart from the expansion inhibitory impact in parental PCa cells, the present examine revealed that ART additionally induces anti-growth and anti-proliferative exercise in DX-resistant DU145, PC3, and LNCaP cells. Accordingly, ART disrupted resistance in different most cancers sorts which have develop into insensitive to standard therapeutic brokers, together with bicalutamide, an androgen receptor antagonist, utilized previously to deal with metastatic castration-resistant prostate most cancers (39). Latest research have demonstrated ART-induced anti-cancer properties in parental and cisplatin-resistant bladder cancers (40) and sunitinib-resistant renal cell carcinomas (41). Consistent with these observations, ART additionally inhibited cell progress and proliferation in tongue (42), breast (43, 44), liver (45), colorectal (46) and esophageal (47) cancers. Furthermore, the current investigation revealed that ART doesn’t limit the expansion of ‘regular’, right here major non-tumor tubular epithelial, cells.

Diminished cell progress and proliferation of the DX-resistant DU145, PC3, and LNCaP and parental LNCaP cells have been related to G0/G1 part arrest and a big discount of S part (all) and G2/M part cells (DU145). Per this, ART-induced anti-proliferative exercise was accompanied by a rise within the G0/G1 part in human epidermoid carcinoma (48), endometrial most cancers (49), bladder most cancers (40) and renal carcinoma (41) cells. In good accordance with the G0/G1 part arrest within the PCa cells, the cell cycle activating proteins CDK1, CDK2, cyclin A, and cyclin B, answerable for S part and G2/M part development, have been down-regulated, additional corroborating the G0/G1 part arrest. DNA replication within the S part is managed by the CDK2/cyclin A fancy (50) and the exercise of the cyclin B/CDK1 complicated is required in the course of the G2/M part (51). Moreover, expression of cyclin D1, which is concerned in regulating G0/G1 part development (52), diminished after publicity to ART.

Apoptotic occasions occurred in parental PC3 and LNCaP cells in addition to within the DX-resistant LNCaP and DU145 cells. In distinction, parental DU145 and DX-resistant PC3 cells didn’t show apoptotic cell demise after 48 h publicity to ART. Thus, the mechanism behind the ART-induced inhibition of progress and proliferation in parental DU145 initially remained obscure. As a consequence, activation of different cell demise signaling was postulated and evaluated as a doable rationalization for these inhibitory results of ART. Certainly, ferrostatin-1, a selective ferroptosis inhibitor, considerably abrogated the anti-proliferative exercise of ART, solely in parental and DX-resistant DU145 cells, indicating ferroptosis induction. In good accordance with our knowledge, it has been proven that ART effectively induced ferroptosis in head and neck (28) in addition to in pancreas (29) most cancers cells. Moreover, ART activated ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, when mixed with sorafenib (53). In distinction, PC3 and LNCaP cells weren’t affected. The truth is, solely the DU145 cell line, among the many chosen PCa cell traces, carries a mutation within the oncogenic KRAS gene, leading to a gene fusion with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2L3 (54). Erastin, a selected ferroptosis inducer, brought about preferential lethality in cells bearing some extent mutation within the oncogenic HRAS(G12V) gene (55). Thus, the KRAS-UBE2L3 fusion protein may result in ART-mediated induction of ferroptosis in DU145 cells. Nevertheless, that is speculative and requires additional investigation. In parental DU145 cells further software of ferrostatin-1 already counteracted ART’s anti-proliferative influence after 24 h. The same impact was evident in DX-resistant DU145 cells after 48 h, indicating a delayed initiation of ferroptosis within the DX-resistant DU145 cells, in comparison with the parental DU145 cells. This delay may clarify the stronger proliferation inhibition after 48 h ART remedy within the parental, in comparison with the DX-resistant DU145 cells.

A number of research have indicated that ART induces DNA injury through oxidative stress and the era of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (56, 57). A fundamental characteristic of ferroptosis is lipid peroxidation of the mobile and organelle membranes, resulting from elevated intracellular ROS, inflicting oxidative cell demise (58–60). Ferroptosis-mediated ROS is thought to be accompanied by a depletion of GSH and the blockade of the antioxidant protection mechanisms with the Methods-xc and GSH-dependent peroxidase, GPX4 (58–60). In good accordance with this, in each parental and DX-resistant DU145 cells considerably decreased GSH ranges have been obvious after publicity to ART, confirming ROS formation beneath ART administration. Equally, ART elevated ROS and decreased GSH in essentially the most aggressive triple-negative breast most cancers cells, leading to intracellular oxidative imbalance and ferroptosis (61). Moreover, ART induced ferroptosis in head and neck most cancers cells by reducing mobile GSH ranges and growing lipid ROS ranges (28). This impact may very well be blocked by co-incubation with ferrostatin-1. GPX4 catalyzes the discount of GSH to oxidized GSSG, utilizing GSH as an important cofactor, thereby lowering ROS to H2O (62). Silencing GPX4 by shRNA, which results in a partial knockdown of GPX4, sensitized fibrosarcoma and renal carcinoma cells to a ferroptosis-induced lethality by erastin (63).Per this, the present examine revealed a big lower of GPX4 expression in each parental and DX-resistant cells after ART remedy, indicating inhibited GPX4 exercise accompanied by absent GSH regeneration and therewith accumulation of ROS.

Because the antitumor results of ART have been obvious in each androgen-sensitive (LNCaP) and androgen-insensitive PCa-cells (PC3 & DU-145), ART’s motion appears to be androgen receptor-independent. Nevertheless, an influence on androgen receptors can’t be completely excluded, as its expression was not evaluated. Different investigators have revealed a discount in androgen receptors after ART remedy in androgen receptor-positive 22rvl cells (19).

5 Conclusions

ART exhibited tumor suppressive potential in regard to the progressive progress of parental and therapy-resistant PCa cells. Cell-type-specific modes of motion have been induced by ART, resulting in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and/or ferroptosis. These actions have been accompanied by impaired expression of cell cycle activating proteins, primarily CDK1, CDK2, cyclin A, cyclin B, and cyclin D1, modulated expression of apoptotic proteins, and a rise in ROS. Due to this fact, ART could maintain promise as a complementary therapeutic possibility in sufferers with superior and even therapy-resistant PCa.

Knowledge Availability Assertion

The unique contributions offered within the examine are included within the article/Supplementary Materials. Additional inquiries will be directed to the corresponding creator.

Creator Contributions

Conceptualization, EJ. Methodology, VB, OV, SM, HE, PS, PB, KS, AT, MP, ZC, JC, and MM. Software program, SM. Validation, OV and SM. Formal evaluation, VB and OV. Investigation, EJ and OV. Assets, EJ, PB, TE, MP, ZC, JC, and MM. Knowledge curation, OV. Writing—authentic draft preparation, OV. Writing—assessment and enhancing, EJ, HE, IT, AH, TE, and MM. Visualization, OV. Supervision, EJ. Challenge administration, EJ. Funding acquisition, EJ, MM, and JC. All authors have learn and agreed to the revealed model of the manuscript.

Funding

This analysis was funded by the Brigitta und Norbert Muth Stiftung, grant quantity 01/2018 (EJ), Hilfe für krebskranke Kinder Frankfurt e.V. (JCJr.), Frankfurter Stiftung für krebskranke Kinder (JCJr), and the Kent Most cancers Belief (MM).

Battle of Curiosity

The authors declare that the analysis was performed within the absence of any industrial or monetary relationships that may very well be construed as a possible battle of curiosity.

Writer’s Word

All claims expressed on this article are solely these of the authors and don’t essentially characterize these of their affiliated organizations, or these of the writer, the editors and the reviewers. Any product which may be evaluated on this article, or declare which may be made by its producer, just isn’t assured or endorsed by the writer.

Acknowledgments

The primary portion of the outcomes offered listed here are a part of the medical physician thesis of VB. on the Division of Urology and Pediatric Urology (College Medical Heart Mainz, Langenbeckstraße 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany). Some components stem from the grasp thesis of PS.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplementary Materials for this text will be discovered on-line at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.789284/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sanda MG, Cadeddu JA, Kirkby E, Chen RC, Crispino T, Fontanarosa J, et al. Clinically Localized Prostate Most cancers: AUA/ASTRO/SUO Guideline. Half I: Threat Stratification, Shared Resolution Making, and Care Choices. J Urol (2018) 199:683–90. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.11.095

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

3. Parker C, Castro E, Fizazi Ok, Heidenreich A, Ost P, Procopio G, et al. Clinicalguidelines@Esmo.Org, E.G.C.E.a. Prostate Most cancers: ESMO Scientific Observe Pointers for Analysis, Therapy and Comply with-Up. Ann Oncol (2020) 31:1119–34. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.06.011

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

4. Clarke NW, Ali A, Ingleby FC, Hoyle A, Amos CL, Attard G, et al. Addition of Docetaxel to Hormonal Remedy in Low- and Excessive-Burden Metastatic Hormone Delicate Prostate Most cancers: Lengthy-Time period Survival Outcomes From the STAMPEDE Trial. Ann Oncol (2019) 30:1992–2003. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz396

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

5. Heck MM, Thalgott M, Retz M, Wolf P, Maurer T, Nawroth R, et al. Rational Indication for Docetaxel Rechallenge in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Most cancers. BJU Int (2012) 110:E635–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11364.x

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

6. Thomas C, Brandt MP, Baldauf S, Tsaur I, Frees S, Borgmann H, et al. Docetaxel-Rechallenge in Castration-Resistant Prostate Most cancers: Defining Scientific Elements for Profitable Therapy Response and Enchancment in Total Survival. Int Urol Nephrol (2018) 50:1821–7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-1963-1

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

7. Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Pointers on Prostate Most cancers. Half II-2020 Replace: Therapy of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Most cancers. Eur Urol (2021) 79:263–82. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.046

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

8. Cornford P, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, De Santis M, Gross T, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG Pointers on Prostate Most cancers. Half II: Therapy of Relapsing, Metastatic, and Castration-Resistant Prostate Most cancers. Eur Urol (2017) 71:630–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.002

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

9. Jang A, Kang DH, Kim DU. Complementary and Different Medication Use and Its Affiliation With Emotional Standing and High quality of Life in Sufferers With a Strong Tumor: A Cross-Sectional Research. J Altern Complement Med (2017) 23:362–9. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0289

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

10. Hierl M, Pfirstinger J, Andreesen R, Holler E, Mayer S, Wolff D, et al. Complementary and Different Medication: A Scientific Research in 1,016 Hematology/Oncology Sufferers. Oncology (2017) 93:157–63. doi: 10.1159/000464248

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

11. Ebel MD, Rudolph I, Keinki C, Hoppe A, Muecke R, Micke O, et al. Notion of Most cancers Sufferers of Their Illness, Self-Efficacy and Locus of Management and Utilization of Complementary and Different Medication. J Most cancers Res Clin Oncol (2015) 141:1449–55. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-1940-3

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

12. Kessel KA, Lettner S, Kessel C, Bier H, Biedermann T, Friess H, et al. Use of Complementary and Different Medication (CAM) as A part of the Oncological Therapy: Survey About Sufferers’ Angle In direction of CAM in a College-Based mostly Oncology Heart in Germany. PloS One (2016) 11:e0165801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165801

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

16. Sarma B, Willmes C, Angerer L, Adam C, Becker JC, Kervarrec T, et al. Artesunate Impacts T Antigen Expression and Survival of Virus-Optimistic Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:919. doi: 10.3390/cancers12040919

17. Morrissey C, Gallis B, Solazzi JW, Kim BJ, Gulati R, Vakar-Lopez F, et al. Impact of Artemisinin Derivatives on Apoptosis and Cell Cycle in Prostate Most cancers Cells. Anticancer Medication (2010) 21:423–32. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328336f57b

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

18. Willoughby JA Sr., Sundar SN, Cheung M, Tin AS, Modiano J, Firestone GL. Artemisinin Blocks Prostate Most cancers Progress and Cell Cycle Development by Disrupting Sp1 Interactions With the Cyclin-Dependent Kinase-4 (CDK4) Promoter and Inhibiting CDK4 Gene Expression. J Biol Chem (2009) 284:2203–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804491200

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

19. Wang Z, Wang C, Wu Z, Xue J, Shen B, Zuo W, et al. Artesunate Suppresses the Progress of Prostatic Most cancers Cells By means of Inhibiting Androgen Receptor. Biol Pharm Bull (2017) 40:479–85. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b16-00908

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

20. Ng DS, Liao W, Tan WS, Chan TK, Loh XY, Wong WS. Anti-Malarial Drug Artesunate Protects In opposition to Cigarette Smoke-Induced Lung Harm in Mice. Phytomedicine (2014) 21:1638–44. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.07.018

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

21. Posner GH, Oh CH, Gerena L, Milhous WK. Terribly Potent Antimalarial Compounds: New, Structurally Easy, Simply Synthesized, Tricyclic 1,2,4-Trioxanes. J Med Chem (1992) 35:2459–67. doi: 10.1021/jm00091a014

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

23. Peng Q, Warloe T, Berg Ok, Moan J, Kongshaug M, Giercksky KE, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Based mostly Photodynamic Remedy. Scientific Analysis and Future Challenges. Most cancers (1997) 79:2282–308. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2282::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-o

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

24. Hamacher-Brady A, Stein HA, Turschner S, Toegel I, Mora R, Jennewein N, et al. Artesunate Prompts Mitochondrial Apoptosis in Breast Most cancers Cells through Iron-Catalyzed Lysosomal Reactive Oxygen Species Manufacturing. J Biol Chem (2011) 286:6587–601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210047

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

25. Efferth T, Giaisi M, Merling A, Krammer PH, Li-Weber M. Artesunate Induces ROS-Mediated Apoptosis in Doxorubicin-Resistant T Leukemia Cells. PloS One (2007) 2:e693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000693

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

26. Michaelis M, Kleinschmidt MC, Barth S, Rothweiler F, Geiler J, Breitling R, et al. Anti-Most cancers Results of Artesunate in a Panel of Chemoresistant Neuroblastoma Cell Strains. Biochem Pharmacol (2010) 79:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.013

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

27. Greenshields AL, Shepherd TG, Hoskin DW. Contribution of Reactive Oxygen Species to Ovarian Most cancers Cell Progress Arrest and Killing by the Anti-Malarial Drug Artesunate. Mol Carcinog (2017) 56:75–93. doi: 10.1002/mc.22474

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

28. Roh JL, Kim EH, Jang H, Shin D. Nrf2 Inhibition Reverses the Resistance of Cisplatin-Resistant Head and Neck Most cancers Cells to Artesunate-Induced Ferroptosis. Redox Biol (2017) 11:254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.010

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

29. Eling N, Reuter L, Hazin J, Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR. Identification of Artesunate as a Particular Activator of Ferroptosis in Pancreatic Most cancers Cells. Oncoscience (2015) 2:517–32. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.160

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

30. Baer PC, Bereiter-Hahn J, Schubert R, Geiger H. Differentiation Standing of Human Renal Proximal and Distal Tubular Epithelial Cells In Vitro: Differential Expression of Attribute Markers. Cells Tissues Organs (2006) 184:16–22. doi: 10.1159/000096947

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

31. Baer PC, Nockher WA, Haase W, Scherberich JE. Isolation of Proximal and Distal Tubule Cells From Human Kidney by Immunomagnetic Separation. Technical Word. Kidney Int (1997) 52:1321–31. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.457

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

32. Michaelis M, Rothweiler F, Barth S, Cinatl J, van Rikxoort M, Loschmann N, et al. Adaptation of Most cancers Cells From Totally different Entities to the MDM2 Inhibitor Nutlin-3 Leads to the Emergence of P53-Mutated Multi-Drug-Resistant Most cancers Cells. Cell Demise Dis (2011) 2:e243. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.129

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

33. Michaelis M, Wass MN, Cinatl J. Drug-Tailored Most cancers Cell Strains as Preclinical Fashions of Acquired Resistance. Most cancers Drug Resistance (2019) 2:447–56. doi: 10.20517/cdr.2019.005

34. Kong Z, Liu R, Cheng Y. Artesunate Alleviates Liver Fibrosis by Regulating Ferroptosis Signaling Pathway. BioMed Pharmacother (2019) 109:2043–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.030

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

35. Ooko E, Saeed ME, Kadioglu O, Sarvi S, Colak M, Elmasaoudi Ok, et al. Artemisinin Derivatives Induce Iron-Dependent Cell Demise (Ferroptosis) in Tumor Cells. Phytomedicine (2015) 22:1045–54. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.08.002

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

36. Zhou Y, Wang X, Zhang J, He A, Wang YL, Han Ok, et al. Artesunate Suppresses the Viability and Mobility of Prostate Most cancers Cells By means of UCA1, the Sponge of Mir-184. Oncotarget (2017) 8:18260–70. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15353

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

37. Deeken JF, Wang H, Hartley M, Cheema AK, Smaglo B, Hwang JJ, et al. A Section I Research of Intravenous Artesunate in Sufferers With Superior Strong Tumor Malignancies. Most cancers Chemother Pharmacol (2018) 81:587–96. doi: 10.1007/s00280-018-3533-8

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

38. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Tropenmedizin, R.u.G.G.e.V.D. Leitlinie: Diagnostik und Therapie der Malaria. Availabe on-line: https://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/element/ll/042-001.html (accessed on 20.01.2022).

39. Nunes JJ, Pandey SK, Yadav A, Goel S, Ateeq B. Focusing on NF-Kappa B Signaling by Artesunate Restores Sensitivity of Castrate-Resistant Prostate Most cancers Cells to Antiandrogens. Neoplasia (2017) 19:333–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.02.002

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

40. Zhao F, Vakhrusheva O, Markowitsch SD, Slade KS, Tsaur I, Cinatl J Jr., et al. Artesunate Impairs Progress in Cisplatin-Resistant Bladder Most cancers Cells by Cell Cycle Arrest, Apoptosis and Autophagy Induction. Cells (2020) 9:2643. doi: 10.3390/cells9122643

41. Markowitsch SD, Schupp P, Lauckner J, Vakhrusheva O, Slade KS, Mager R, et al. Artesunate Inhibits Progress of Sunitinib-Resistant Renal Cell Carcinoma Cells By means of Cell Cycle Arrest and Induction of Ferroptosis. Cancers (Basel) (2020) 12:3150. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113150

42. Xiao Q, Yang L, Hu H, Ke Y. Artesunate Targets Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma through Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Dependent Oxidative Harm and Akt/AMPK/Mtor Inhibition. J Bioenerg Biomembr (2020) 52:113–21. doi: 10.1007/s10863-020-09823-x

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

43. Chen Ok, Shou LM, Lin F, Duan WM, Wu MY, Xie X, et al. Artesunate Induces G2/M Cell Cycle Arrest By means of Autophagy Induction in Breast Most cancers Cells. Anticancer Medication (2014) 25:652–62. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000089

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

44. Greenshields AL, Fernando W, Hoskin DW. The Anti-Malarial Drug Artesunate Causes Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis of Triple-Unfavourable MDA-MB-468 and HER2-Enriched SK-BR-3 Breast Most cancers Cells. Exp Mol Pathol (2019) 107:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2019.01.006

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

46. Jiang F, Zhou JY, Zhang D, Liu MH, Chen YG. Artesunate Induces Apoptosis and Autophagy in HCT116 Colon Most cancers Cells, and Autophagy Inhibition Enhances the Artesunateinduced Apoptosis. Int J Mol Med (2018) 42:1295–304. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3712

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

47. Fei Z, Gu W, Xie R, Su H, Jiang Y. Artesunate Enhances Radiosensitivity of Esophageal Most cancers Cells by Inhibiting the Restore of DNA Harm. J Pharmacol Sci (2018) 138:131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2018.09.011

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

48. Jiang Z, Chai J, Chuang HH, Li S, Wang T, Cheng Y, et al. Artesunate Induces G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest and Iron-Mediated Mitochondrial Apoptosis in A431 Human Epidermoid Carcinoma Cells. Anticancer Medication (2012) 23:606–13. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328350e8ac

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

49. Tran KQ, Tin AS, Firestone GL. Artemisinin Triggers a G1 Cell Cycle Arrest of Human Ishikawa Endometrial Most cancers Cells and Inhibits Cyclin-Dependent Kinase-4 Promoter Exercise and Expression by Disrupting Nuclear Issue-Kappab Transcriptional Signaling. Anticancer Medication (2014) 25:270–81. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000054

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

50. Zhang H, Kobayashi R, Galaktionov Ok, Seaside D. p19Skp1 and p45Skp2 Are Important Components of the Cyclin a-CDK2 s Section Kinase. Cell (1995) 82:915–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90271-6

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

53. Li ZJ, Dai HQ, Huang XW, Feng J, Deng JH, Wang ZX, et al. Artesunate Synergizes With Sorafenib to Induce Ferroptosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Acta Pharmacol Sin (2021) 42:301–10. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0478-3

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

54. Wang XS, Shankar S, Dhanasekaran SM, Ateeq B, Sasaki AT, Jing X, et al. Characterization of KRAS Rearrangements in Metastatic Prostate Most cancers. Most cancers Discovery (2011) 1:35–43. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0022

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

55. Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC, Stockwell BR. Identification of Genotype-Selective Antitumor Brokers Utilizing Artificial Deadly Chemical Screening in Engineered Human Tumor Cells. Most cancers Cell (2003) 3:285–96. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00050-3

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

56. Beccafico S, Morozzi G, Marchetti MC, Riccardi C, Sidoni A, Donato R, et al. Artesunate Induces ROS- and P38 MAPK-Mediated Apoptosis and Counteracts Tumor Progress In Vivo in Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma Cells. Carcinogenesis (2015) 36:1071–83. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv098

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

57. Gopalakrishnan AM, Kumar N. Antimalarial Motion of Artesunate Includes DNA Harm Mediated by Reactive Oxygen Species. Antimicrob Brokers Chemother (2015) 59:317–25. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03663-14

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

58. Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee ED, Hayano M, et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of Cystine-Glutamate Change Induces Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Ferroptosis. Elife (2014) 3:e02523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02523

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

59. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Type of Nonapoptotic Cell Demise. Cell (2012) 149:1060–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

61. Li Z, Wu X, Wang W, Gai C, Zhang W, Li W, et al. Fe(II) and Tannic Acid-Cloaked MOF as Provider of Artemisinin for Provide of Ferrous Ions to Improve Therapy of Triple-Unfavourable Breast Most cancers. Nanoscale Res Lett (2021) 16:37. doi: 10.1186/s11671-021-03497-z

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar

63. Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada Ok, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, et al. Regulation of Ferroptotic Most cancers Cell Demise by GPX4. Cell (2014) 156:317–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010

PubMed Summary | CrossRef Full Textual content | Google Scholar